Irish Sepulchral Mounds, Cairns, etc.

Modes of Internment practised by the Pagan Irish—Cinerary Urns—Tumulus and Sepulchral Chamber of Newgrange—Mound of Dowth, and Its Sepulchral Chambers—Stone Basin—Mound of Rathmullan—Bee-hive Chamber—Ancient Enclosure

From A Hand-book of Irish Antiquities by William F. Wakeman

« Pillar Stones | Contents | Raths or Duns »

HE pagan Irish appear to have made use of two modes of sepulture, viz., by interring the body whole, in a horizontal or perpendicular position, and by cremation. In the latter practice, when the body had become sufficiently calcined, the ashes were placed in an urn of clay or stone, which was then deposited within an artificial chamber formed of large uncemented stones, over which it was the custom to raise a cairn, or an earthen mound. Cinerary urns, however, have been found within the area of stone circles, and frequently in the plain ground, simply enclosed in a small kist, or turned mouth downward upon a slate. They have also been found in tumuli, not many feet from the surface; even in mounds that, in their centre, contained other, and probably much more ancient deposits. In cases of interment, the grave appears generally to have been formed of large flat stones placed edgewise, and enclosing a space barely sufficient to contain the body; over these similar stones were placed, the whole lying a little beneath the surface of the earth. The cromlech appears to have been but a larger kind of tomb.

HE pagan Irish appear to have made use of two modes of sepulture, viz., by interring the body whole, in a horizontal or perpendicular position, and by cremation. In the latter practice, when the body had become sufficiently calcined, the ashes were placed in an urn of clay or stone, which was then deposited within an artificial chamber formed of large uncemented stones, over which it was the custom to raise a cairn, or an earthen mound. Cinerary urns, however, have been found within the area of stone circles, and frequently in the plain ground, simply enclosed in a small kist, or turned mouth downward upon a slate. They have also been found in tumuli, not many feet from the surface; even in mounds that, in their centre, contained other, and probably much more ancient deposits. In cases of interment, the grave appears generally to have been formed of large flat stones placed edgewise, and enclosing a space barely sufficient to contain the body; over these similar stones were placed, the whole lying a little beneath the surface of the earth. The cromlech appears to have been but a larger kind of tomb.

A most interesting account of burial in an upright position is referred to in the Book of Armagh, where King Loeghaire is represented as telling St. Patrick that his father Niall used to tell him never to believe in Christianity, but to retain the ancient religion of his ancestors, and to be interred in the hill of Tara, like a man standing up in battle, and with his face turned to the south, as if bidding defiance to the men of Leinster.

NEWGRANGE MOUND, OR CAIRN

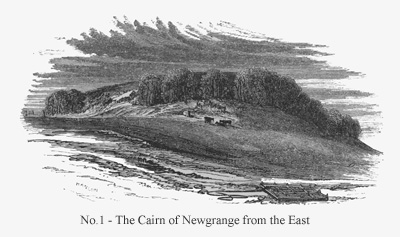

The cairn of Newgrange, in the county of Meath, lying at a distance of about four miles and a half from Drogheda, is perhaps, without exception, the most wonderful monument of its class now existing in any part of western Europe. In one point, at least, it may challenge comparison with any Celtic monument known to exist, inasmuch as the mighty stones of which its gallery and chambers, of which we shall speak hereafter, are composed, exhibit a profusion of ornamental design, consisting of spiral, lozenge, and zig-zag work, such as is usually found upon the torques, urns, weapons, and other remains of pagan times in Ireland. We shall here say nothing of its probable antiquity, as it is anterior to the age of alphabetic writing; and indeed it would be in vain to speculate upon the age of a work situate upon the banks of the Boyne, which, if found upon the banks of the Nile, would be styled a pyramid, and perhaps be considered the oldest of all the pyramids of Egypt.

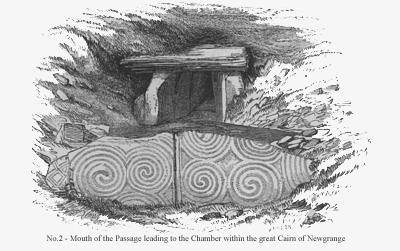

The cairn (see woodcut No. 1), which even in its present ruinous condition measures about seventy feet in height, from a little distance presents the appearance of a grassy hill partially wooded; but upon examination, the coating of earth is found to be altogether superficial, and in several places the stones, of which the hill is entirely composed, are laid bare. A circle of enormous stones, of which eight or ten remain above ground, anciently surrounded its base; and we are informed that upon the summit an obelisk, or enormous pillar stone, formerly stood. The opening represented in the cut No. 2, was accidentally discovered about the year 1699 by labouring men employed in the removal of stones for the repair of a road. The gallery, of which it is the external entrance, extends in a direction nearly north and south, and communicates with a chamber or cave nearly in the centre of the mound.

This gallery, which measures in length about fifty feet, is at its entrance from the exterior four feet high, in breadth at the top three feet two inches, and at the base three feet five inches.

These dimensions it retains, except in one or two places where the stones appear to have been forced from their original position, for a distance of twenty-one feet from the external entrance. Thence towards the interior its size gradually increases, and its height, where it forms the chamber, is eighteen feet. Enormous blocks of stone, apparently water-worn, and supposed to have been brought from the mouth of the Boyne, form the sides of the passage; and it is roofed with similar stones. The ground plan of the chamber is cruciform, the head and arms of the cross being formed by three recesses, one placed directly fronting the entrance, the others east and west, and each containing a basin of granite. The sides of these recesses are composed of immense blocks of stone, several of which bear a great variety of carving, supposed by some to be symbolical.

These dimensions it retains, except in one or two places where the stones appear to have been forced from their original position, for a distance of twenty-one feet from the external entrance. Thence towards the interior its size gradually increases, and its height, where it forms the chamber, is eighteen feet. Enormous blocks of stone, apparently water-worn, and supposed to have been brought from the mouth of the Boyne, form the sides of the passage; and it is roofed with similar stones. The ground plan of the chamber is cruciform, the head and arms of the cross being formed by three recesses, one placed directly fronting the entrance, the others east and west, and each containing a basin of granite. The sides of these recesses are composed of immense blocks of stone, several of which bear a great variety of carving, supposed by some to be symbolical.

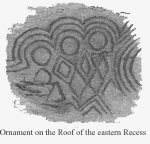

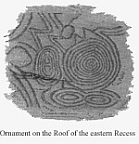

The engravings represent various characteristic selections from the work upon the roof of the eastern recess, in the construction and decoration of which a great degree of care appears to have been exercised. An engraving upon a stone forming the northern external angle of the western recess is supposed to be an inscription; but, even could any satisfactory reading of it be given, its authenticity is doubtful, as it has been supposed to have been forged by one of the many dishonest Irish antiquaries of the last century.

The engravings represent various characteristic selections from the work upon the roof of the eastern recess, in the construction and decoration of which a great degree of care appears to have been exercised. An engraving upon a stone forming the northern external angle of the western recess is supposed to be an inscription; but, even could any satisfactory reading of it be given, its authenticity is doubtful, as it has been supposed to have been forged by one of the many dishonest Irish antiquaries of the last century.

The same stone upon its eastern face exhibits what appears to have been intended as a representation of a fern or yew branch. An ornament, or hieroglyphic, of a similar character, was found within an ancient Celtic tomb at Locmariaker, in Brittany,—see Archaeologia, vol. xxv. p. 233. It is a very remarkable fact that the majority of these carvings must have been executed before the stones upon which they appear had been placed in their present positions. Of this there is abundant evidence in the eastern recess, where we find the lines continued over portions of the stones which it would be impossible now to reach with an instrument, and which form the sides of mere interstices.

The same stone upon its eastern face exhibits what appears to have been intended as a representation of a fern or yew branch. An ornament, or hieroglyphic, of a similar character, was found within an ancient Celtic tomb at Locmariaker, in Brittany,—see Archaeologia, vol. xxv. p. 233. It is a very remarkable fact that the majority of these carvings must have been executed before the stones upon which they appear had been placed in their present positions. Of this there is abundant evidence in the eastern recess, where we find the lines continued over portions of the stones which it would be impossible now to reach with an instrument, and which form the sides of mere interstices.

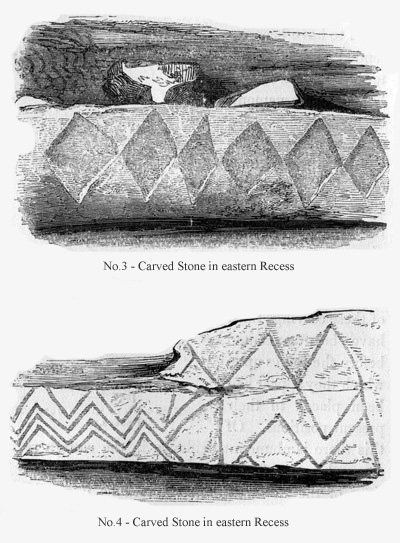

The cuts marked 3 and 4 represent some decorations of a very peculiar character which appear upon the sides of the eastern recess.

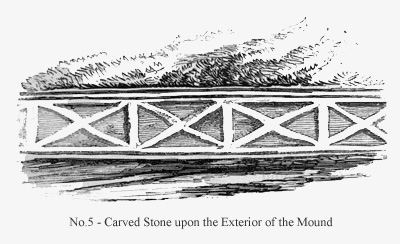

No. 5 represents a stone now lying upon the surface of the mound, a little above the opening described in page 22.

The lower portions of the walls of the chamber are composed of large uncemented stones, placed in an upright

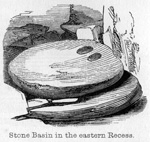

position, over which are others laid horizontally, each course projecting slightly beyond that upon which it rests, and so on, until the sides so closely approximate that a single stone suffices to close in and complete the roof, which, in its highest part, is twenty feet above the present level of the floor. The length of the passage and chamber, from north to south, is seventy-five, and the breadth of the chamber, from east to west, twenty feet. Of the urns or basins contained in the various recesses, that to the east is the most remarkable. It is formed of a block of granite, and appears to have been set upon, or rather within, another, of somewhat larger dimensions. Of its form the annexed wood-cut will give a just idea. Two small circular cavities have been cut within its interior, as represented above; a peculiarity not found in either of the others, which are of much ruder construction, and very shallow. Subjoined is a representation of the basin in the western recess.

position, over which are others laid horizontally, each course projecting slightly beyond that upon which it rests, and so on, until the sides so closely approximate that a single stone suffices to close in and complete the roof, which, in its highest part, is twenty feet above the present level of the floor. The length of the passage and chamber, from north to south, is seventy-five, and the breadth of the chamber, from east to west, twenty feet. Of the urns or basins contained in the various recesses, that to the east is the most remarkable. It is formed of a block of granite, and appears to have been set upon, or rather within, another, of somewhat larger dimensions. Of its form the annexed wood-cut will give a just idea. Two small circular cavities have been cut within its interior, as represented above; a peculiarity not found in either of the others, which are of much ruder construction, and very shallow. Subjoined is a representation of the basin in the western recess.

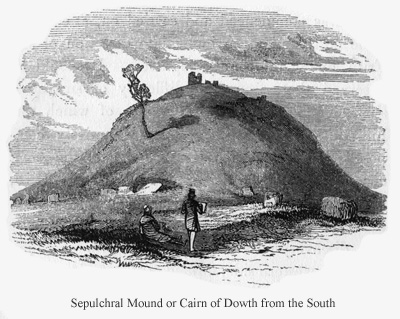

In the neighbourhood of the Newgrange tumulus are two other monuments of the same class, and of an extent nearly equal: the "Hills" of Nowth and Dowth, or, as they are called by the Irish, Cnoabh and Dubhath; the former lying about one mile to the westward of Newgrange, and the latter, of which the subjoined is an illustration, at a similar distance in the opposite direction.

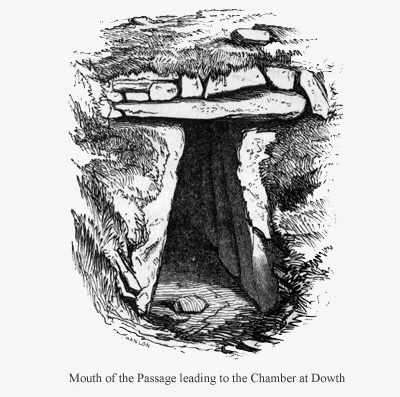

Of the internal arrangement of this huge cairn, little, until very recently, was known beyond the fact that it was different from that of the monument last described, inasmuch as, instead of one great gallery leading directly towards the centre of the pile, there appeared here the remains of two passages in a very ruinous state, and completely stopped up, neither of which, however, seemed to have conducted towards a grand central chamber. The Committee of Antiquities of the Royal Irish Academy having, in the course of last autumn (1847), obtained permission from the trustees of the Netterville Charity, the present proprietors of the Dowth estate, to explore the interior of the tumulus, the work was commenced and carried on, at considerable cost, under the immediate direction of Mr. Frith, one of the county engineers. It should be observed that, from the difficulty of sinking a shaft among the loose, dry stones of which this hill, like that of Newgrange, is entirely composed, Mr. Frith, in order to arrive at the great central chamber which was supposed to exist, adopted the plan of making an open cutting from the base of the mound, towards its centre. The first discovery was that of a cruciform chamber, upon the western side, formed of stones of enormous size, every way similar to those at Newgrange, and exhibiting the same style of decoration. A rude sarcophagus, bearing a great resemblance to that in the eastern recess at Newgrange, of which we have given an illustration in page 30, was found in the centre. It had been broken into several pieces, but the fragments have all been found, and placed together, so as to afford a perfect idea of its original form. In clearing away the rubbish with which the chamber was found nearly filled, the workmen discovered a large quantity of the bones of animals in a half-burned state, and mixed with small shells.

A pin of bronze and two small knives of iron were also discovered. With respect to instruments of iron being found in a monument of so early a date, we may observe, that in the Annals of Ulster there occurs a record of this mound, as well as of several others in the neighbourhood, having been searched by the Northmen of Dublin as early as A. D. 862, "on one occasion that the three kings, Amlaff, Imar, and Ainsle, were plundering the territory of Flann, the son of Coaing;" and it is an interesting fact that the knives are precisely similar, in every respect, to a number discovered, together with a quantity of other antiques, in the bog near Dunshaughlin, and which there is reason to refer to a period between the ninth and the beginning of the eleventh centuries. Upon the chamber being cleared out, a passage twenty-seven feet in length was discovered, the sides of which incline considerably, leading in a westerly direction towards the side of the mound, and composed, like the similar passage at Newgrange, of enormous stones, placed edgeways, and covered in with large flags. The chamber, though of inferior size to that at Newgrange, is constructed so nearly upon the same plan, that a description of the one might almost serve for that of the other. The recesses, however, do not contain basins, and a passage extending in a southerly direction, communicating with a series of small crypts, forms here another peculiarity. A huge stone, in height nine, in breadth eight feet, placed between the northern and eastern recesses, is remarkable for the singular character of its carving.—See cut No. 1.

Upon the chamber being cleared out, a passage twenty-seven feet in length was discovered, the sides of which incline considerably, leading in a westerly direction towards the side of the mound, and composed, like the similar passage at Newgrange, of enormous stones, placed edgeways, and covered in with large flags. The chamber, though of inferior size to that at Newgrange, is constructed so nearly upon the same plan, that a description of the one might almost serve for that of the other. The recesses, however, do not contain basins, and a passage extending in a southerly direction, communicating with a series of small crypts, forms here another peculiarity. A huge stone, in height nine, in breadth eight feet, placed between the northern and eastern recesses, is remarkable for the singular character of its carving.—See cut No. 1.

A portion of the work upon this stone bears great resemblance to Ogham writing.—See p. 19. A sepulchral chamber, of a quadrangular form, the stones of which bear a great variety of carving (among which the cross, a symbol which neither in the old nor the "new" world can be considered as peculiar to Christianity, is conspicuous), has been discovered upon the southern side of the mound. Here, as elsewhere, during the course of excavation, the workmen found vast quantities of bones, half-burned, many of which proved to be human; "several unburned bones of horses,* pigs, deer, and birds, portions of the heads of the short-horned variety of the ox, and the head of a fox."† They also found a star-shaped amulet of stone, a ring of jet, several beads, and some bones fashioned like pins. Among the stones of the upper portion of the cairn were discovered a number of globular balls of stone, the size of small eggs, which Dr. Wilde supposes probably to have been sling-stones. Up to the time of our writing, no other chambers have been found; but as the works are still in progress, further discoveries may yet be made; and even now the gentlemen of the Academy may feel that their undertaking has been most successful. A double circle of stones appears anciently to have surrounded this cairn. Of these the greater number lie buried, but in summertime their position, particularly after a long continuance of sunny weather, is shewn by the remarkably dry and withered appearance of the grass above them.

Here, as elsewhere, during the course of excavation, the workmen found vast quantities of bones, half-burned, many of which proved to be human; "several unburned bones of horses,* pigs, deer, and birds, portions of the heads of the short-horned variety of the ox, and the head of a fox."† They also found a star-shaped amulet of stone, a ring of jet, several beads, and some bones fashioned like pins. Among the stones of the upper portion of the cairn were discovered a number of globular balls of stone, the size of small eggs, which Dr. Wilde supposes probably to have been sling-stones. Up to the time of our writing, no other chambers have been found; but as the works are still in progress, further discoveries may yet be made; and even now the gentlemen of the Academy may feel that their undertaking has been most successful. A double circle of stones appears anciently to have surrounded this cairn. Of these the greater number lie buried, but in summertime their position, particularly after a long continuance of sunny weather, is shewn by the remarkably dry and withered appearance of the grass above them.

Among the trees between the mound of Dowth and the mansion are the remains of a small sepulchral chamber; and a little to the east of the house the student will find a grand specimen of the ancient military encampment, or rath.

« Pillar Stones | Contents | Raths or Duns »

NOTES

* At Rathmullan, in the county of Down, similar bones, mixed with cinders and charcoal, and covered over with an earthen mound, occur.

† See Dr. Wilde's interesting paper on the Boyne, in the Dublin University Magazine for December, 1847.