Irish Crosses

Varieties of the Early Crosses—Examples at Monasterboice—Their Sculpture and Decorations—Monumental Stones—Ancient Graves—Examples at Saint John's Point, arranged in Circles—Town-y-Chapel, Holyhead

From A Hand-book of Irish Antiquities by William F. Wakeman

« Churches | Contents | Round Towers »

HE graves of many of the early Irish saints are marked by stones differing in nowise from the pagan pillar stone, except that in some instances they are sculptured with a cross, plain or within a circle. This style of monument appears to have been succeeded by a rudely-formed cross, the arms of which are little more than indicated, and which is usually fixed in a socket, cut in a large flat stone. Such crosses rarely exhibit any kind of ornament, but occasionally, even in very rude examples, the upper part of the shaft is hewn into the form of a circle, from which the arms and the top extend; and those portions of the stone by which the circle is indicated are frequently perforated, or slightly recessed A fine plain cross of this style may be seen in the graveyard of Tullagh, County Dublin; and there is an early decorated example near the church of Finglas, in the same county. Crosses, highly sculptured, appeal to have been very generally erected between the ninth and twelfth centuries; but there are no examples of a later period remaining, if we except a few bearing inscriptions in Latin or English, which belong to the close of the sixteenth, or to the seventeenth century, and which can hardly be looked upon as either Irish or ancient.

HE graves of many of the early Irish saints are marked by stones differing in nowise from the pagan pillar stone, except that in some instances they are sculptured with a cross, plain or within a circle. This style of monument appears to have been succeeded by a rudely-formed cross, the arms of which are little more than indicated, and which is usually fixed in a socket, cut in a large flat stone. Such crosses rarely exhibit any kind of ornament, but occasionally, even in very rude examples, the upper part of the shaft is hewn into the form of a circle, from which the arms and the top extend; and those portions of the stone by which the circle is indicated are frequently perforated, or slightly recessed A fine plain cross of this style may be seen in the graveyard of Tullagh, County Dublin; and there is an early decorated example near the church of Finglas, in the same county. Crosses, highly sculptured, appeal to have been very generally erected between the ninth and twelfth centuries; but there are no examples of a later period remaining, if we except a few bearing inscriptions in Latin or English, which belong to the close of the sixteenth, or to the seventeenth century, and which can hardly be looked upon as either Irish or ancient.

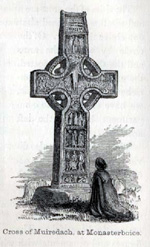

From the rude pillar stone marked with the symbol of our faith, enclosed within a circle, the emblem of eternity, the finely proportioned and elaborately sculptured crosses of a later period are derived. In the latter, the circle, instead of being simply cut upon the face of the stone, is represented by a ring, binding, as it were, the shaft, arms, and upper portion of the cross together. The beautiful remains of this class at Monasterboice, near Drogheda, though the finest now remaining in Ireland, are nearly equalled by some scores of others scattered over the whole island. Indeed, in our crosses alone we have evidence sufficient to satisfy the most sceptical of the skill which the Irish had attained in more of the arts than one, during the earlier ages of the Church. They may be regarded, not only as memorials of the piety and munificence of a people whom ignorance and prejudice have too often sneered at as barbarous, but also as the finest works of sculptured art, of their period, now existing. Two crosses at Monasterboice remain in their ancient position, and are well preserved, though one of them, in particular, bears distinct evidence of a systematic attempt having been made to destroy it. A third has been broken to pieces, the people say by Cromwell, but its head, and part of the shaft, remaining uninjured, the fragment has been set in the ancient socket.

From the rude pillar stone marked with the symbol of our faith, enclosed within a circle, the emblem of eternity, the finely proportioned and elaborately sculptured crosses of a later period are derived. In the latter, the circle, instead of being simply cut upon the face of the stone, is represented by a ring, binding, as it were, the shaft, arms, and upper portion of the cross together. The beautiful remains of this class at Monasterboice, near Drogheda, though the finest now remaining in Ireland, are nearly equalled by some scores of others scattered over the whole island. Indeed, in our crosses alone we have evidence sufficient to satisfy the most sceptical of the skill which the Irish had attained in more of the arts than one, during the earlier ages of the Church. They may be regarded, not only as memorials of the piety and munificence of a people whom ignorance and prejudice have too often sneered at as barbarous, but also as the finest works of sculptured art, of their period, now existing. Two crosses at Monasterboice remain in their ancient position, and are well preserved, though one of them, in particular, bears distinct evidence of a systematic attempt having been made to destroy it. A third has been broken to pieces, the people say by Cromwell, but its head, and part of the shaft, remaining uninjured, the fragment has been set in the ancient socket.

The larger of the two nearly perfect crosses measures twenty-seven feet in height, and is composed of three stones The shaft, at its junction with the base, is two feet in breadth, and one foot and three inches in thickness. It is divided upon the western side by fillets into seven compartments, each of which contains two or more figures cut with very bold effect, but much worn by the rain and wind of nearly nine centuries. The sculpture of the first compartment, beginning at the base, has been destroyed by those who attempted to throw down the cross. The second contains five figures, of which one, apparently the most important, is presenting a book to another, who receives it with both hands, while a large bird seems resting upon his head. The other figures in this compartment represent females, one of whom holds a child in her arms.

Compartments 3, 4, 5, and 6, contain three figures each, evidently the Apostles, and each figure is represented with a book. The seventh division, which runs into the circle forming the head of the cross, is occupied by two figures; and immediately above them is a representation of our Saviour crucified, while a soldier upon each side is piercing his body with a spear. To the right and to the left of the figure of our Saviour, other sculptures appear. The figures upon the right arm of the cross are represented apparently in the act of adoration. The action of those upon the left is obscure, and in consequence of the greater exposure of the upper portion of the stone to the weather, the sculpture which it bears is greatly worn, and almost effaced.

The sides of the cross are ornamented with figures and scroll work placed alternately in compartments one above the other. Of the circle by which the arms and the shaft are connected, the external portions are enriched; and, as an example, we have engraved the compartment beneath the left arm.

The sides of the cross are ornamented with figures and scroll work placed alternately in compartments one above the other. Of the circle by which the arms and the shaft are connected, the external portions are enriched; and, as an example, we have engraved the compartment beneath the left arm.

The eastern side is also divided into compartments occupied by sculptures, which may refer to Scripture history.

The smaller cross is most eminently beautiful. The figures and ornaments with which its various sides are enriched appear to have been executed with an unusual degree of care, and even of artistic skill. It has suffered but little from the effects of time. The sacrilegious hands which attempted the ruin of the others appear to have spared this, and it stands almost as perfect as when, nearly nine centuries ago, the artist, we may suppose, pronounced his work finished, and chiefs and abbots, bards, shanachies, warriors, ecclesiastics, and perhaps many a rival sculptor, crowded round this very spot, full of wonder and admiration for what they must have considered a truly glorious, and perhaps unequalled work. An inscription in Irish, upon the lower part of the shaft, desires "a prayer for Muiredach, by whom was made this cross;" but, as Dr.Petrie,by whom the inscription has been published, remarks, there were two of the name mentioned in the Irish Annals as having been connected with Monasterboice, one an abbot, who died in the year 844, and the other in the year 924, "so that it must be a matter of some uncertainty to which of these the erection of the cross should be ascribed." There is reason, however, to assign it to the latter, "as he was a man of greater distinction, and probably wealth, than the former, and therefore more likely to have been the erector of the crosses." Its total height is exactly fifteen feet, and it is six in breadth at the arms. The shaft, which at the base measures in breadth two feet six inches, and in thickness one foot nine inches, diminishes slightly in its ascent, and is divided upon its various sides, by twisted bands, into compartments, each of which contains either sculptured figures or tracery of very intricate design, or animals, probably symbolical.

pronounced his work finished, and chiefs and abbots, bards, shanachies, warriors, ecclesiastics, and perhaps many a rival sculptor, crowded round this very spot, full of wonder and admiration for what they must have considered a truly glorious, and perhaps unequalled work. An inscription in Irish, upon the lower part of the shaft, desires "a prayer for Muiredach, by whom was made this cross;" but, as Dr.Petrie,by whom the inscription has been published, remarks, there were two of the name mentioned in the Irish Annals as having been connected with Monasterboice, one an abbot, who died in the year 844, and the other in the year 924, "so that it must be a matter of some uncertainty to which of these the erection of the cross should be ascribed." There is reason, however, to assign it to the latter, "as he was a man of greater distinction, and probably wealth, than the former, and therefore more likely to have been the erector of the crosses." Its total height is exactly fifteen feet, and it is six in breadth at the arms. The shaft, which at the base measures in breadth two feet six inches, and in thickness one foot nine inches, diminishes slightly in its ascent, and is divided upon its various sides, by twisted bands, into compartments, each of which contains either sculptured figures or tracery of very intricate design, or animals, probably symbolical.

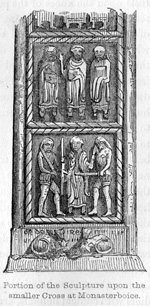

The figures and other sculptures retain, almost unimpaired, their original sharpness and beauty of execution. The former are of great interest, as affording an excellent idea of the dress, both ecclesiastical and military, of the Irish during the ninth or tenth century. As an example we have engraved the two lower compartments upon the west side. Within the circular head of the cross, upon its eastern face, our Saviour is represented sitting in judgment. A choir of angels occupy the arm to the right of the figure. Several are represented with musical instruments, among which the ancient Irish harp may be seen. It is small and triangular, and rests upon the knees of the performer, who is represented in a sitting posture. The space to the left of our Saviour is crowded with figures, several of which are in an attitude of despair. They are the damned; and an armed fiend is driving them from before the throne. The compartment immediately beneath bears a figure weighing in a pair of huge scales a smaller figure, the balance seeming to preponderate in his favour One who appears to have been weighed, and found wanting, is lying beneath the scales in an attitude of terror. The next compartment beneath represents apparently the adoration of the wise men. The star above the head of the infant Christ is distinctly marked. The third compartment contains several figures, the action of which we do not understand. The signification of the sculpture of the next following compartment is also very obscure. A figure seated upon a throne or chair is blowing a horn, and soldiers with conical helmets, armed with short, broad-bladed swords, and with small circular shields, appear crowding in. The fifth and lowest division illustrates the Temptation and the Expulsion. The figures upon the western face of the shaft, of which we have engraved two compartments, probably relate to the early history of Monasterboice.

As an example we have engraved the two lower compartments upon the west side. Within the circular head of the cross, upon its eastern face, our Saviour is represented sitting in judgment. A choir of angels occupy the arm to the right of the figure. Several are represented with musical instruments, among which the ancient Irish harp may be seen. It is small and triangular, and rests upon the knees of the performer, who is represented in a sitting posture. The space to the left of our Saviour is crowded with figures, several of which are in an attitude of despair. They are the damned; and an armed fiend is driving them from before the throne. The compartment immediately beneath bears a figure weighing in a pair of huge scales a smaller figure, the balance seeming to preponderate in his favour One who appears to have been weighed, and found wanting, is lying beneath the scales in an attitude of terror. The next compartment beneath represents apparently the adoration of the wise men. The star above the head of the infant Christ is distinctly marked. The third compartment contains several figures, the action of which we do not understand. The signification of the sculpture of the next following compartment is also very obscure. A figure seated upon a throne or chair is blowing a horn, and soldiers with conical helmets, armed with short, broad-bladed swords, and with small circular shields, appear crowding in. The fifth and lowest division illustrates the Temptation and the Expulsion. The figures upon the western face of the shaft, of which we have engraved two compartments, probably relate to the early history of Monasterboice. The head of the cross upon this side is sculptured with a representation of the Crucifixion, very similar to that upon the head of the larger cross, but the execution is better. Its northern arm underneath bears the representation of a hand extended, and holding what Wright, in his Louthiana, calls a cake, probably the Host. Of the broken cross, which is extremely plain, we have engraved a boss, placed within its circle.

The head of the cross upon this side is sculptured with a representation of the Crucifixion, very similar to that upon the head of the larger cross, but the execution is better. Its northern arm underneath bears the representation of a hand extended, and holding what Wright, in his Louthiana, calls a cake, probably the Host. Of the broken cross, which is extremely plain, we have engraved a boss, placed within its circle.

An early monumental stone remains in the cemetery, a few yards to the north of the less ancient church. The inscription is in the Irish language and character, and reads in English, "A prayer for Ruarchan."

A simple flag-stone, inscribed with a name, and sculptured with the sacred symbol of Christianity, such as it was the custom among the early Irish Christians to place over the grave of an eminent man, forms a striking contrast to the tablets which too often disfigure the walls of our cathedral and parish churches. Many remains of this class lie scattered among the ancient and often neglected graveyards of Ireland, but they are every day becoming more rare, as the country stone-cutters, by whom they are regarded with but slight veneration, frequently form out of their materials modern tombstones, defacing the ancient inscription. We have engraved an example hitherto unnoticed, from Inis Cealtra, an island in Lough Derg, an expansion of the Shannon.

to place over the grave of an eminent man, forms a striking contrast to the tablets which too often disfigure the walls of our cathedral and parish churches. Many remains of this class lie scattered among the ancient and often neglected graveyards of Ireland, but they are every day becoming more rare, as the country stone-cutters, by whom they are regarded with but slight veneration, frequently form out of their materials modern tombstones, defacing the ancient inscription. We have engraved an example hitherto unnoticed, from Inis Cealtra, an island in Lough Derg, an expansion of the Shannon.

In several cemeteries found in connexion with the earlier monastic establishments of Ireland, graves formed after the pagan fashion, of flat stones placed edgeways in an oblong figure, and covered with large flags, frequently occur. But that in several instances the stones at either end of the enclosure have been sculptured with a cross, they might be supposed to indicate the site of a pagan cemetery which the early Christians, for obvious reasons, had hallowed by the erection of a chapel. The direction of the grave is generally east and west, but in the cemetery adjoining the very early church at Saint John's Point, in the county of Down, and elsewhere, the cists are arranged in the form of a circle, to the centre of which the feet of the dead converge.

A similar mode of interment, which occurs at Town-y-Chapel, near Holyhead, in Wales, is referred to in the Archaeological Journal, vol. iii.; and it is worthy of remark, that the place where the graves are found appears to have been the scene of a battle, fought about A. D. 450, in which many Irishmen were slain.