Two Royal Abbeys on the Western Lakes (Cong and Inismaine)

Lecture delivered in the Town Hall, Tuam, 29th December, 1904.

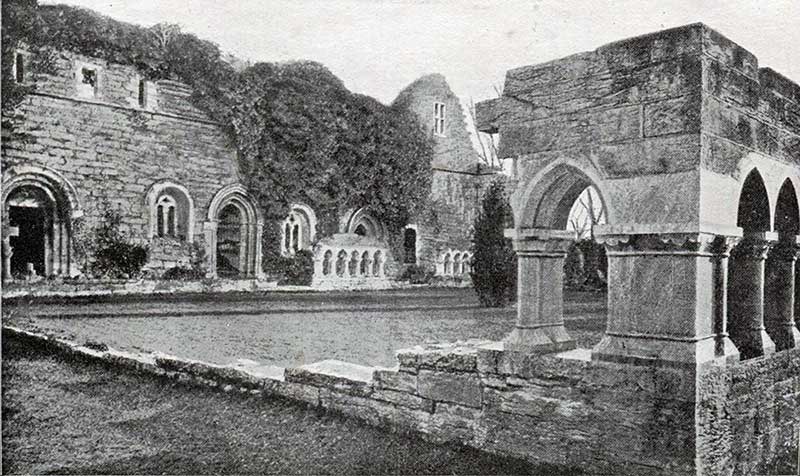

Cong Abbey

THE natural beauty of our Western Lake-land is greatly enhanced by the historical associations, especially of a religious character, that still haunt its rifled shrines and ruined castles. But there are two of these ruins which, more than all the rest, deceive the earnest attention of every Irishman who loves the ancient glories of his native land—I mean the Abbey of Cong on Lough Corrib, and the Abbey of Inismaine on Lough Mask.

From every point of view they are full of interest—the religious, the historical, the architectural, the picturesque. Memorials that bring back the past, visions of vanished glories, ghosts of bardic heroes, glimpses of kingly warriors and cowled monks and stately dames and tragic deeds—all these rise up before the thoughtful mind in the cloisters of Cong and the chancel of Inismaine more naturally, I think, than in any other place in Ireland.

The first thing that will strike every intelligent observer is the peerless beauty of the sites which those old monks chose for their religious houses and churches. No doubt they had then what we have never had in our time—a full and free choice, for the Irish kings and chieftains rarely grudged to give their best to God. But the monks then knew how to chose the best, which is more, I think, than can be said of some of us now; and they always chose sites of great natural beauty. Certainly they did so in the case of Cong and Inismaine.

The two Abbeys were closely connected. The latter, in fact, seems—at least in the twelfth century—to have been a branch-house of the former. There is not more than four miles distance between them, yet I venture to say there is not in all Ireland a district of more varied beauty and greater historical interest. No feature that enriches a landscape is wanting. Two noble wide-spreading lakes, like inland seas, dotted over with myriad islands and flanked by noble mountains; far-reaching woodlands; quiet groves and sunny waters; foliage of the richest green; early blooms never blighted by the nipping frost; underground rivers from lake to lake, suddenly bursting out from their sunless caves in mighty rushing floods; hill and dale and rock and mound intermingled in bewildering variety—all these scenic charms the old monks could enjoy in an evening’s stroll around their beautiful homes.

At Cong the noble river rushed before their very doors. They had an abundance of purest water—the greatest of all human needs for health and pleasure; they had abundance of fish for fasting days, and they had the great lake before their eyes, lit up by every ray of sunlight in summer, and grander still, perhaps, in winter when lashed into foam by the wild rush of the storms from the western hills. Such was Cong; and its beautiful daughter in Inismaine stood in the midst of scenes no less varied and striking.

It is not to be wondered at that a land so rich in nature’s choicest gifts should have been the battle-ground of warring races, and the choicest prize of conquering kings. And such it was in very truth from the morning prime of our island story down almost to our own times. The undulating plain between the lakes is dotted over with the burial mounds and monumental pillar stones of the warriors who fell in the first great battle between hostile races recorded in our history—that is, the famous battle of South Moyturey, or rather, Moytura.

This is not the place to give an account of that stricken field. If we had nothing but the bardic tale that tells us of it, no doubt the whole story would be set down as a pure romance. But as Sir William Wilde has shown, the bardic tale is confirmed in all its main features by the evidence of existing monuments, so that we can, partly by the tale and partly by the monuments, trace with tolerable accuracy the whole course of the three days’ battle, and the varying fortunes of victors and vanquished.

There is one grand monument still remaining “in proud defiance of all-conquering Time”—Carn Eochy, which is undoubtedly the grave mound of the Belgic King Eochy, who was slain on the third day of the fight. It overlooks Lough Mask and Inismaine, and is one of the finest monuments of its kind to be found anywhere in Ireland. It was raised over the dead warrior by his devoted followers more than 3,000 years ago, and it is likely to last at least 3,000 years more. Every other work of human hands around has either totally disappeared or is a shapeless ruin; but the grand old monument of the Firbolgic King seems to be as enduring as the lakes and mountains of the West.

It is still a most conspicuous object, towering over the whole storied plain, and as I gazed at it fronting the West, standing alone with strength and pride, I could hardly divest my mind of the idea that the great old Belgic King was not wholly dead, but from his royal mound still kept watch and ward over the fate of the descendants of the warriors who survived the fatal day of Moytura. They fled, it would seem, into the bogs and mountains and islands of the West. They are still, beyond any doubt, in the lands which were too poor to attract the greedy conquerors.

These conquerors, the Tuatha de Danaan, were themselves shortly afterwards conquered by the Scotic or Milesian races, and they have not left even a trace behind. No Irish family, high or low, traces its ancestry to them. They have no existence, except as the fairies of the forts, in the imagination of the people. The Scots or Milesians in their time had to give place to the Normans through all that fair western land around the Abbeys; the Norman, later on, had to yield to the Cromwellian, and the Norman keeps are now more desolate than the burial mounds of the Firbolgs.

Strangest of all, the ownership of those fair lands, which the Firbolgs held 3,000 years ago, is likely to revert in our own time to the sons of the ancient tillers of the soil, to whom all the nobles of every blood—Milesian, Norman, and Cromwellian—will find it necessary to yield up the ownership—to the very vassals whose sires were in utter bondage, and have worked it for some 3,000 years. Hardly anything more strange, in my opinion, and more just, has happened in the annals of human vicissitude; but the fact is there, and it is undeniable, although it is somewhat removed from the immediate subject of my story, to which I now return.

The primitive Monastery of Inismaine was founded about one hundred years before the greater Monastery of Cong. A glance at the map—the Ordnance map if possible—will show you how it was situated. In the olden times, before the lakes were drained, there were three distinct islands running in a line from the eastern shore near Lough Mask Castle far into the lake—that is, Iniscoog, Inismaine, or the Middle Island, and Inishowen, which stood out far in the deep water. But now they form really one great promontory, and in summer weather can be reached on foot quite easily dryshod, and there is even a fair road by a raised causeway, over a half-broken bridge, from Iniscoog into Inismaine.

Inishowen, the most western of the group, is a flattish cone of green land bordered with a fringe of wood by the lake shore, and rising to a height of 142 feet from the level of the lake. On the summit there is an ancient dun, now so thickly overgrown with shrubs that on the occasion of my visit I found it impossible to effect an entrance, but from its outer edge, looking west and south-west over the lake to the giant hills beyond, there is one of the finest views I have ever seen. That ancient dun was called Dun Eoghain, and from the same old king this western island itself was called by the name, which it still bears, Inishowen.

This Eoghan—known in our annals as Eoghan Beul—was King of Connaught during the first quarter of the sixth century. He was a great grandson of the famous King Dathi, of whom you have all heard something, and inherited the bravery as well as the blood of that grand warrior king. He was mortally wounded in a fierce battle against the men of the North near Sligo, in the year A.D. 537. The Four Masters tell us that the Northerns carried off his head with them from the field of battle, with many other spoils, to their own country. But the Life of St. Ceallach (his son) tells a different story —that he survived the fight for three days, and that he told his own soldiers to bury him standing up in his grave, fronting the hostile North, with shield and spear in his hands, and that so long as he remained there facing the foe the Northerns would never gain a victory over the men of the West, the Hy-Fiachrach of the Moy.

And so it came to pass. But when the Northerns heard it they came stealthily by night, took up the body of the dead king, and carrying it with them over the Sligo River buried it ignobly near Hazelwood, in low ground, with the face downwards. So the spell was broken, and the dead warrior cowed the foe no more. Now, this warrior king dwelt in his dun on Inishowen about the year 525, when a great saint called Cormac, coming from the South of Ireland, made his way to the royal dun, and asked the king for a little land on which to build his cell and monastery in that neighbourhood.