Some Irish Graves in Rome

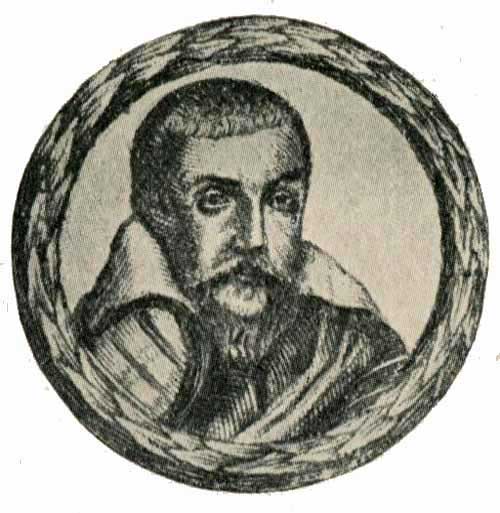

Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone

IT was on Monday morning, October 29th, 1900, that we (the Irish pilgrims then in Rome) assembled at nine o’clock for Mass in St. Peter’s Church in Montorio, anciently known as the Janiculum, not far from St. Peter’s in the Vatican. I myself was celebrant of the Mass, and the evening before, in the Roman Academia, on the Corso, I had explained to the pilgrims something of the history of the graves we were to visit. After Mass the pilgrims gathered round the twin gravestones, which were fringed, I think, with ivy leaves, and most devoutly recited the De Profundis for the souls whose ashes lay beneath their feet, and whose names are inscribed on the marble flags. Then they examined the various paintings and monuments in the church, especially the beautiful little temple in the courtyard of the Franciscan monastery adjoining, which was erected on the very spot where St. Peter is said to have suffered martyrdom. I heard some one of the Roman bystanders say, “Why do they all come here?”—this church was not one of the great Basilicas which the pilgrims were bound to visit—but some one else replied that great Irishmen were buried there, and these pilgrims came to visit their tombs, and say a prayer for their souls. My purpose in this paper, is to tell you who are the great Irishmen referred to thus vaguely, and why they came to be buried in St. Peter’s church in Montorio, beneath those marble slabs.

Now, this church is most interesting for many reasons. It stands on the slope of the Janiculum, on the western bank of the Tiber, and overlooks the whole city of Rome. From this point you can see every church and palace and ancient ruin throughout the city—the huge dome of St. Peter’s on the left; in front the Capitol, surmounted with the Convent of Ara Coeli; then towards the right the ruins of the Palatine and the Coliseum, and all the other ancient monuments around the great church of the Lateran. These are in the foreground immediately beneath the spectator; but further on, as Martial tells us of his own time, you can see the Seven Royal Hills of Rome, and judge the whole extent of the city, bounded in the blue distance by the Alban Hills on the south, and the higher hills of Tusculum stretching far away to the north-east. The yellow Tiber flows beneath in two great bends from north to south, and directly in front, but a little to the right, was the ancient wooden bridge across the river, which “the Dauntless Three” held so bravely against the Etruscan army that poured down upon them from this very hill on which we stood. This Janiculum was in olden times outside the city proper. The lower ground towards the river was then inhabited for the most part by the Jews, and in the time of Nero by the Christians, who dwelt amongst them, and with whom they were often confounded.

This was, perhaps, the reason why the slope of the hill where the church now stands was chosen as the scene of St. Peter’s crucifixion. It was outside the city, close to the quarter of the turbulent Jews, and hence a fitting place to execute a “malefactor” of the hated race. The Saint had been confined in the Mamertine Prison near the Forum; but he was taken thence and led up to this conspicuous spot above the Jewish quarter, overlooking, as was fitting, all Royal Rome; and there the cross was erected in that very hole from which the lay Brother now takes up for you a little of the golden sand. “Let me not be crucified like my Master,” he said to the soldiers. “I am unworthy of it; let my body be fastened to the cross with my head down.” So he was crucified with his head down, as Eusebius and St. Jerome, quoting from more ancient writers, expressly tell us. “Happy man,” says St. Chrysostom, “with his feet erect to walk straight into Heaven.”

The body of St. Peter was taken from this place of execution by the Priest Marcellinus and interred in a quiet spot on the slope of the Vatican Hill, about a half a mile further north on the same side of the river, probably the place where the holy priest then dwelt, and offered the Holy Sacrifice. Over his tomb there grew up a church which was greatly enlarged in the time of Constantine the Great, and was finally rebuilt in its present unapproachable grandeur during the sixteenth century by men like Michael Angelo, Bramante, and others, whose equals have never since appeared in the world of art and architecture. It was this Bramante who designed the beautiful little temple—Tempietta—in the Courtyard of St. Peter’s, in Montorio, over the very spot where, as Mangan says, “the martyr saint” was crucified, and which is reverently visited by the pilgrims of every nationality who go to Rome. It was Raphael, too, perhaps the greatest of all painters, who painted his famous Transfiguration to be an altar-piece for this Church of Montorio, and it continued over the high altar until 1797, when it was, like many other works of art, stolen by the sacrilegious French from Rome. It was afterwards restored, and is now one of the greatest of the art treasures in the Vatican; so that from the religious and artistic point of view this church has many points of interest for the pilgrim. It was built by order of the Catholic Sovereigns Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain about the year 1500, and given in charge to a community of Spanish Franciscans. Their representatives are there still, but, as the Superior told me after our cup of coffee, they are very poor, for, like the Italian religious, they have been left destitute by their own Government, and now live on the fruits of their garden and the scanty alms of the faithful. It would be a real charity to help the guardians of the Earls’ graves.

Interior of Church of St. Peter in Montorio

But for the Irish pilgrims the graves of the Northern Earls were, of course, the great centre of attraction, and no patriotic Irishman who goes to Rome ever leaves them unvisited.

“Two Princes of the line of Conn

Sleep in their cells of clay beside O’Donnell Roe;

Three Royal youths, alas! are gone,

Who lived for Erin’s weal, but died for Erin’s woe!

Ah! could the men of Ireland read

The names these noteless burial-stones display to view,

Their wounded hearts afresh would bleed,

Their tears gush forth again—their groans resound anew.”

So sang the Bard of Tyrconnell who accompanied the Earls, as poor Clarence Mangan has translated his woeful song; and even still it is hard for an Irishman to view these graves unmoved—that is, an Irishman who knows the whole sad story of glory, disaster, and death. I propose to read for you the names on these noteless burial-stones. One stone on the left tells us that Prince Rory O’Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnell, whom the poet calls “O’Donnell Roe,” after many battles fought, and many labours endured for his faith and country, was driven an exile from Ireland and received with hospitality and affection by the Pope in Rome, where to the grief of all who looked for his return, he died on the 29th of July, 1608, in the 33rd year of his age. His brother Caffar, the companion of his dangers and his exile, followed him to the grave on the 15th October following, at the age of twenty-five. It is added that their eldest brother, Prince Hugh O’Donnell, had predeceased them six years, and was buried by the royal care of Philip III. of Spain, at Valladolid, on the 10th September, 1602. The second stone records that Hugh, Baron of Dungannon, the eldest son of Prince Hugh O’Neill the Great, after fighting many years against the heretics for his religion and country, like his uncle, the Earl of Tyrconnell, became an exile, and died, like him, an early death, on the 1st October, 1609, in the 24th year of his age. At a later period—seven years later—the great Hugh himself went to his rest, and although it is not stated on the slab, it is certain that he was buried beside his son, the Baron of Dungannon, and a simple inscription recording his death was inscribed on the tomb. I did not see the inscription over the Great Hugh, but Father Murphy quotes it as follows:—

Hic quiescunt

Hugonis Principis O’Neill

Ossa.

So they sleep side by side in death far away from green Tyrconnell, those noble princes of the North, so closely allied in blood, in virtue, and in deeds of valour on many a well-fought field, the names of which are among the most glorious recorded in the chequered annals of our sad island story.