St. Patrick in the Far West of Ireland

A lecture delivered in the Town Hall, Westport.

I PURPOSE to give a sketch of St. Patrick’s missionary labours here in the far West, especially in relation to his famous fast on the Holy Mountain, which still bears his name. It is a subject full of interest for all Irishmen, and especially tor you who dwell under the very shadow of the Sacred Hill, which has been always regarded as the Mount Sinai of Ireland. I shall only attempt to trace the Apostle’s footsteps through what is known as West Mayo—to do more at present would be impossible.

ROUTE THROUGH MAYO TO THE REEK

Having founded the church of Donaghpatrick (which still bears his name), in Magh Seola, near Headford, in the modern County Galway, the Saint crossed into Mayo, most probably at Shrule, where there was an ancient and famous ford over the Black River. In that territory, then called Conmaicne, we are told that he founded four-cornered churches; and as stone was abundant, they were doubtless built of that material. One was called Ard Uiscon, which may be Donaghpatrick itself. Another is called the small middle church—cellola media—which is doubtless Kilmainebeg. It is exactly the same name in Irish, and the old churchyard there probably marks the site of the Patrician Church. Therein he left as nuns the sisters of the Bishop Felart of the Hy Ailell, that is the modern barony of Tirerrill, in the County Sligo. The Bishop himself dwelt at Donaghpatrick. He also founded other churches in the same region—for he went westward, even beyond Cong—but they cannot now be identified. Returning, he proceeded north into Magh Cerae, and founded a church about a mile north of Kilmaine, on the road to Hollymount. It still bears its ancient name, for Kilquire is only another form of the Cuil Core in the Book of Armagh. We are told that he baptised very many in that place, and doubtless the Holy Well is there still. The old church, however, has entirely disappeared, and nothing but the graveyard remains.

Patrick then went northwards into Magh Foimsen. This we take to be the great plain between Hollymount and Lough Carra. We are told that he found there two brothers, chiefs of the district, one of whom—Derglam—sent his herdsman to slay Patrick, but the other brother, Luchta by name, forbade him, whereupon Patrick blessed Luchta, assuring him that there would be bishops and priests of his race there always; “but the seed of thy brother,” said he, “will be accursed and soon disappear.” He left there a priest, Conan by name, but it is impossible now to identify the site of this church. It was probably somewhere near Ballyglass.

St. Patrick then went westward to a place called Tobar Stringle, in the desert. He must have passed by the famous well since called Tobar Patrick; but he did not stay there on his first visit to the place. The name Stringle is now corrupted into “Triangle,” and there, we are told, he spent two Sundays; but it is not stated that he built a church there. A little later on he founded the church at Ballintober. From Tobar Stringle we are told that Patrick made a short excursion northwards to Magh Raithin, which is the plain around Islandeady lake; but it was a short visit—although he founded a church there—for it is immediately added in the Book of Armagh that he went to the men of Umall, that is to Aghad Fobair, where, as the Book remarks, “Bishops dwell.” This goes to show that, at the time the Book of Armagh was written Aghad Fobair, now strangely corrupted into Aghagower, was an Episcopal See with jurisdiction over the men of Umall.

The account given of this ancient church in the Book of Armagh, supplemented by the account in the Tripartite, is extremely interesting.

PATRICK AT AGHAGOWER

Aghagower, County Mayo

Aghagower is finely situated on the margin of a clear stream, surrounded by a group of sheltering hills. When St. Patrick and his religious family encamped on the grassy margin of the stream, it would appear that the first who came to seek him was a fair young maiden, Mathona by name, the daughter of the Chief—so far as we can judge—who after instruction and baptism, begged to receive the religious veil at the hands of Patrick, which request he gladly granted her. Then the maiden’s father also came to be instructed by Patrick with his household; and Patrick finding him to be a very holy man, of gentle, patient disposition—his wife appears to have been dead—had him duly instructed and consecrated Bishop of that place. Moreover, he gave his convert a new name. Before he was called Senach, but Patrick called him Agnus Dei—God’s Lamb—and the name was appropriate, as the three petitions he asked of Patrick clearly show—first, that he might never sin—mortally of course—under grade, that is after his ordination; secondly, in his humility he asked that his church should not take its name from himself, so that instead of being called Cill-Senach, it has always retained the old name, Aghad Fobair or Aghagower; and lastly, he asked Patrick that the years taken from his own life, if God so willed it, might be added to the age of his son, Aengus, whom also Patrick ordained a priest. Moreover, Patrick, with his own hand, wrote a Catechism or Alphabet, as it is called, of the Christian Doctrine for the young priest, that he might first be instructed himself, and be thus qualified to teach others, and he added that holy bishops of their seed would be there for ever. It is clear that the Saint greatly loved this holy Senach the Bishop, with his virgin daughter, Mathona, and her brother Aengus. I am inclined to think he spent the whole winter of 440-441 with them at Aghagower, and he came to love the place greatly, and wished to remain there, if it was God’s will.

“I would choose,” he said,

“To remain here on a little spot of land.

After faring round churches and

Waters I am weary, and would go no farther.”

It was no wonder indeed he was weary, for he was then advanced in years. He had preached the Gospel and founded churches from Slemish in Antrim to Tara, and from Tara all the way across the country to the far West. Seven years he had already spent founding churches, and crossing rivers, living for the most part in the open, oftentimes in great hardship and much suffering. Would God permit him to spend the remnant of his days with the Lamb of God and his holy family, beside that pleasant stream, and within the shelter of these encircling hills? But no; such was not God’s high will. The angel came to Patrick and told him:—

“Thou shalt have everything round which thou shalt go,

Every land,

Both mountains and churches,

Both glens and woods,

After faring round churches and waters,

Though thou art weary, thou shalt go.”

Yes, indeed, round the whole island he had to go, to the very summit of its soaring hills, across its estuaries and rushing waters, over its spreading plains, through its roughest woods and glens, from the very summit of the Reek, round the wild shores of the northern seas, through the plains of Kildare and the hills of Wicklow, over all the Munsters to the Shannon mouth—he was to go over them all preaching and baptising—but they were all to be his own for ever, and no one would ever be allowed by God to snatch them from his hand.

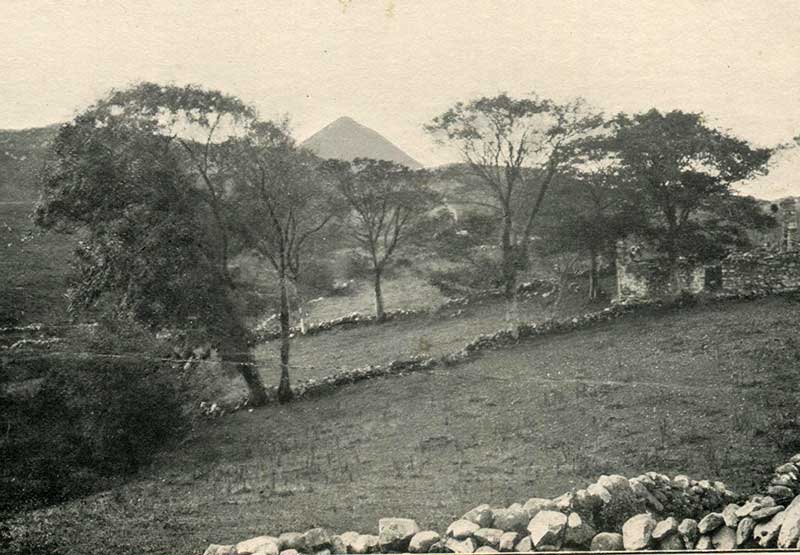

Soaring summit, as seen from afar

With sorrow, therefore, but in perfect obedience he went still farther west to surmount that soaring cone that he saw so often from Aghagower, rising heavenward in the blue distance over the western sea—beautiful at all times, but especially when the sinking sun lit up its rugged flanks with a glory that seemed to pour down from heaven itself upon the Holy Mountain. There he would commune alone with God, like Moses on Sinai, like Elias on Carmel, like the Saviour Himself on the Judean hills; there he would fortify his soul for the great work before him; there he would pray for the people whom, in his own words, “the Lord had given him at the ends of the earth,” and not for them only, but for their children down to their latest generation at the day of doom.