Early Christian Ireland (6)

As life at home became increasingly difficult for learned men new colleges of Irish began to spring up abroad, and Würzburg, Ratisbon, Fulda, Mayence (Mainz), Constance, and Nürnberg were all crowded with Irish students. They have left behind them many precious manuscripts, the fruit of their learning and patience.

In the Imperial Library at Vienna is a copy of the Epistles of St Paul transcribed by a Donegal monk of Ratisbon in 1079. His name, Marianus “Scotus,” shows the country of his birth, and his book was written “for his pilgrim brethren” who joined him from Ireland. Seven of his immediate successors were natives from the North of Ireland.

Another Irish monk of the same name is associated with the Irish abbeys of Cologne and Fulda. He was educated at Moville in Co. Down, but, leaving his native land, he became an enclosed monk of the abbey of St Martin at Cologne. Though living as a solitary he wrote there a History of the World and various tracts of a controversial nature. His reputation spread, and when Siegfried, the Superior of Fulda Abbey, visited Cologne in 1058 he induced Marianus to return with him and take up his residence at Fulda. He became for the second time a professed ‘incluse’ in May 1059, taking up his abode in a cell in which another Irish incluse had lived and died sixteen years before. He died at Mayence, having followed his friend Abbot Siegfried thither, the remaining thirteen years of his life being passed in seclusion. All this we learn from his own diary, which has fortunately been preserved.

A touching marginal note in a copy of his History gives a glimpse of the feelings which passed through the mind of an Irish scribe when, in foreign lands, he received tidings of events passing at home. It reads:

‘It is pleasant for us to-day, O Maelbrigte [i.e., Marianus], incluse in the inclusory of Mayence, on the Thursday before the feast of Peter, in the first year of my obedience to the Rule; namely, the year in which Dermot, King of Leinster, was slain.[60] And this is the first year of my pilgrimage from Scotia [Ireland]. And I have written this book for love of the Scots all, that is, the Irish, because I am myself an Irishman.’

At home the growing power of the Church had, even so early as the days of St Columcille, led to a struggle between the founders of monasteries and the central authority of Tara. The abbots began to exercise an authority independent of the secular arm and claimed, among other powers, the right to shelter criminals behind the ‘law of sanctuary,’ refusing to give them up to justice. Thus a merciful provision, intended to shelter an accused man from the vengeance of his pursuers until his case had been lawfully tried, was interpreted into a defiance of all legal punishment, the abbots in this way claiming an authority superior to that of the State even in matters not directly concerning the Church.

The question was fought out by a test case in the reign of Dermot MacCarroll (Cearbhall), High King of Ireland about 538–565, a man of just aims and high ideals and determined to uphold the authority of the state. The story has taken the form of a parable in which the twelve chief saints of Ireland, as representing the Church, solemnly excommunicate Dermot by ringing of bells and “fasting upon” him.[61] Their action led to the downfall of Dermot and, with him, of the central supreme authority of Tara. After his time its position waned, and it was deserted as the seat of government. Thus the kingship was weakened just at the moment when a strong government would have been invaluable to the country.

The last feis, or triennial festival, of Tara is recorded in the reign of Dermot. The Calendar of Aengus, composed late in the Norse period, speaks of “Tara’s mighty town with her kingdom’s splendour” as having perished, though the chief monastic foundations, in spite of Danish assaults, still survived, and “a multitude of champions of wisdom abode yet in great Armagh.”

But though Tara was deserted the name and title of Áird-rí continued up to the reign of Rory O’Conor, who submitted to Henry II, and during the Norse period a succession of powerful princes occupied the throne.

Among signs of advance was the checking by St Columcille of the overgrown numbers of the bards, who were accustomed to go about the country in large bodies demanding entertainment and impoverishing the population. The exemption of women from warfare was obtained by St Adamnan, or Eunan (d. 704); and the adoption by the Irish Church of the customs and discipline of the Catholic Church in such matters as the date of keeping Easter and the form of the tonsure was largely secured by the persistent efforts of the same reformer. His powerful influence was exercised both at Iona (Hi), of which he was abbot, and in Ireland, where he held two important Synods, one at Armagh and another at Tara, where spots still known as the “Tent” and “Chair” of Adamnan are shown. He, like his great predecessor at Iona, St Columcille, was a Donegal man, and he wrote the most authoritative life of the founder, besides a book on the Holy Land highly praised by Bede. He was, as his writings show, a man of force and imagination.

The state of the country during the close of the seventh and the eighth centuries declined with the decline of the restraining influence of the monastic schools, which had to a large extent replaced that of the secular arm. Disputed successions and enfeebled princes combined to produce a condition of disorder, and the gloom and misery of the period was accentuated by frequent and terrible visitations of pestilence which spared neither princes nor abbots, while the common people were swept away in vast numbers. Abbots of Clonard, Fore, Clonmacnois, and other monasteries, died of it. About 666–669 four abbots of Bangor, Co. Down, succumbed to it in succession. These plagues were followed by a great mortality among the cattle, which added the misery of famine to that of sickness. Extreme frosts are said to have occurred at the same time.

With the passing away of the founders of the greater monasteries the reverence in which these institutions were held seems to have declined. Early in the eighth century began that sacrilegious system of burning the monasteries which the Northmen copied but did not originate. In the period immediately preceding the first recorded Norse descents there is not a year in which the destruction of some old foundation is not noted. For instance, in 774 Armagh, Kildare, and Glendalough were burned. In 777 Clonmacnois was destroyed, in 778 again Kildare, in 783 Armagh and Mayo, in 787 Derry, in 788 Clonard and Clonfert, besides numerous smaller monasteries and churches.[62]

The Danish fury shows us nothing worse than this. Quarrels and actual conflicts between the brethren were frequent. Both monks and students were armed and obliged to attend the warlike expeditions of their chiefs in the same way as other subjects; it is perhaps not surprising that, being trained and expected to fight, they should often have turned their arms against each other. They even appear in Church councils fully armed.[63]

It was not until 803 that the clergy were legally exempted from hostings and wars. But a custom sanctioned by time did not easily die out; we shall find the clergy taking an active part in tribal warfare up to the beginning of the tenth century, though by that time a feeling seems to have been growing up that it was unseemly for monks and clergy to appear on the battlefield.

Never had Ireland been in a weaker condition morally and politically than at the moment when the foreign invader first arrived upon her shores; never was she less prepared to resist the fierce attacks of the Northmen whose conquering arms, spreading westward, fell at the close of the eighth century on the undefended coasts of Ireland.

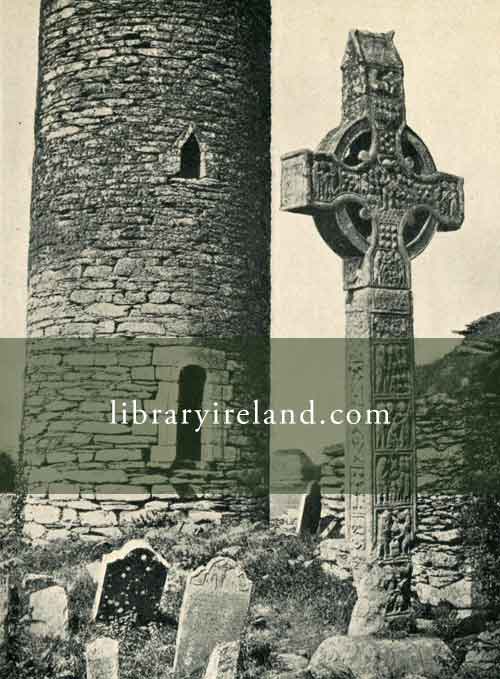

Monasterboice Round Tower and Cross (a.d. 921)

But a great need called out the finer elements in the nation, and, in spite of the terror of the Norse incursions, the period was one of revival. A succession of purposeful rulers resisted with energy the onsets of the Northmen, and the gradual amalgamation of the two peoples brought to each some elements which were needed for the permanent benefit of both nations.

The Danish period in Ireland, usually regarded as one of destruction and fury only, was, in fact, one of distinct advance both in material and intellectual conditions. It found Ireland an open country without large towns or solid fortifications, its chief centres the groups of simple huts gathered round the monastic foundations or along the river-mouths. The close of the Norse occupation left her with a number of walled towns, the beginnings of the larger towns of the present day, with fleets capable of penetrating to the Hebrides or Man, and with a commerce that made cities such as Dublin and Limerick centres of wealth and activity. Stone-built bridges, churches, and round towers showed an advanced style of building and the use of the true arch brought about a revolution in architecture; stone buildings also began to replace the old stockaded forts of the native princes.

From the same period come many of the sweetest lyrics that Ireland has ever produced and a large body of prose literature. The most important religious poem of Ireland, the Psalter of the Verses (Saltair na Rann), relating Biblical events from the creation of the world to the final judgment, and containing a hundred and fifty poems in imitation of the Psalter, was composed toward the close of the tenth century.

It may be called the Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained of early Ireland. Few Irish poems are written on so extended a plan. To reach this state of renewed life the country had to go through a baptism of fire; but, comparing the Ireland of the eighth century with that of the eleventh, there is no question but that a great step forward had been taken, if not in the direction of internal peace at least in the direction of external prosperity.