The Geraldines: The House of Desmond and the House of Kildare (2)

The death of Desmond loosened the bonds which had up to this time held the Anglo-Norman lords of the South attached to the Crown. It showed how difficult it was for even the most esteemed among them to keep in favour with the Government of his country if he were known to act justly and mercifully toward his Irish tenants. Such acts of humanity could easily be represented as “aiding the King’s enemies” by anyone maliciously inclined toward the offender.

The representatives of these great houses were in a difficult position; they felt themselves and were, indeed, looked upon as neither Irish nor English. They were “Irish to the English and English to the Irish.” Close as they were to their adopted country in their sympathies, they had not yet forgotten their English origin and allegiance.

The immediate result of Desmond’s judicial murder was an outbreak by his sons; the first of those devastating rebellions which in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were to reduce the fertile province of Munster to a desert. They wasted the country up to the gates of Dublin.

Tiptoft was recalled for maladministration, and not even the Queen’s letter, which he produced, could purchase his life; he had to “make satisfaction for the angry ghost of Desmond.” By his execution “God was held to have avenged this treachery,” and the King made the largest offers of pardon and restitution to the young men who had taken up arms to avenge the death of their father. His letters were so conciliatory that on reading them the Desmonds decided to lay down their arms, receiving in return extended privileges and large additions to their lands in Kerry, with the town and castle of Dungarvan. Four of them in turn succeeded to the earldom, and they were said to be “wyse and politicke men” who advanced the position of their house at the expense of their Irish neighbours and to the envy of their friends.

Meanwhile, the House of Kildare was also playing a leading part in the history of the country. John FitzThomas FitzGerald, sixth Baron of Offaly, created Earl of Kildare by a patent of Edward II dated May 16, 1316, was in the fourth generation from Maurice FitzGerald (d. 1176), the invader of Ireland and founder of the family fortunes. His great-grandfather Gerald, son of the invader, had erected Maynooth Castle and fixed his seat firmly in Kildare; and Maurice, son of Gerald, held the high post of Justiciar in 1229 and 1232.

The family had proved themselves good servants of the Crown, both in the wars with Bruce in Ireland and with the Scots in Scotland, and had steadily advanced in the royal favour.

Thomas Fitzjohn FitzGerald, who died in 1328, had held the post of sheriff for County Kildare, and was twice Justiciar, presiding in that capacity at the Dublin Parliament of 1324 at which the nobles pledged themselves to support the Crown. His son Richard died, a boy of twelve, in 1331, and the earldom devolved on the youngest brother Maurice (1318–90), who became the fourth Earl. Much of his life was occupied in supporting the opposition led by the Earl of Desmond to the new policy of d’Ufford and Sir John Morice, which aimed at the superseding of the English born in Ireland, such as the Geraldines themselves were, by English born in and brought over from England.

Like Desmond he was pursued with malignancy by the anglicizing Deputy. He was enticed to Dublin and arrested at the Council table; but, as we have said, he was released next year, and he accompanied Edward III to the siege of Calais in 1347, being knighted by him for his services. He was sent back to Ireland as Justiciar in 1356. In spite of being closely watched by English Viceroys jealous of their superior influence, the Kildares maintained their position as the leading magnates of Ireland and were steadily supported by successive sovereigns.

From 1455 to 1459 Thomas FitzGerald, the seventh Earl (d. 1477), acted as Deputy for Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, and welcomed him to Ireland on his flight from the Lancastrians. He it was who built the dyke round the now narrowed English Pale, from which it took its name. For its defence he founded the “Brotherhood of St George,” a body of archers and spearmen, and excluded from the garrisons all disloyal Irish. He lived in perilous times; the Lancastrians in vain sought to intrigue with the Irish against him; but he could not escape the bitter animosity of the Deputy Tiptoft, and became involved in the attainder of Desmond at Drogheda. But his attainder was reversed by the King and repealed at the Parliament of 1468, and Thomas was reappointed Deputy and remained in office till 1475.

On his death in 1477 he was succeeded by the eighth Earl, Garrett or Gerald, known as the “Great Earl of Kildare.” The latter was appointed Deputy in the following year, but the disputes between his family and the Butlers rose to such a height that Edward IV resolved to set aside both rivals to the position of honour, and sent over Lord Grey of Codnor as Deputy in Kildare’s place. Kildare refused to acknowledge his authority, alleging that the letters dismissing him were only sealed with the King’s private signet and were not official. He called a Council at Naas, which passed an Act authorizing him to adjourn or prorogue Parliament at his pleasure, and the curious spectacle was witnessed of two rival Deputies refusing to acknowledge each other and presiding over rival Parliaments.

Annoyed at these feuds, the King summoned before him both the Earl and Grey; but Grey, tired of the contest, retired from office, and Kildare, in the manner of his forefathers, returned with a new commission. He ruled with vigour and justice “his name alone aweing his enemies more than an army.” He is described as tall of stature and of a goodly presence; and, unlike the “secret and drifty” Ormonde, he was “open and plain, hardly able to rule himself when he was moved; in anger not so sharp as short, being easily aroused and sooner appeased.”[13]

He carried his arms into the country of the O’Mores, with whom his family were constantly at war, and he took part in the Ulster wars on the side of his son-in-law, Conn O’Neill. He married his daughters into the houses of Irish chiefs and Norman representatives alike, Lady Eleanor marrying the MacCarthy Reagh; Lady Alice, Conn O’Neill; Lady Eustacia, the Lord of Clanricarde; and Lady Margaret, in the vain hope of healing the breach between the two families, wedded Sir Piers (or Pierce) Butler, who later became the eighth Earl of Ormonde and first Earl of Ossory.

This lady, who was known as Mairgread Gerroid, or sometimes playfully as Magheen, or “Little Margaret,” on account of her lofty stature and character, has left long traditions behind her. Like her father, the “Great Countess of Ormonde” was a woman of remarkable ability, “able for wisdom to rule a realm, had not her stomach overruled herself.” She set herself to reclaim her husband’s country “from the sluttish and unclean Irish custom to the English habits, bedding, housekeeping, and civility”; but her marriage failed of its prime object, for the feuds between her father’s and her husband’s family soon broke out more furiously than ever.

The house of Ormonde was now at the height of its power; it was the only Anglo-Irish family that rivalled the Geraldines and from which, besides their own, successive Deputies were chosen. Sir Piers was twice Deputy, once in 1521 and later in 1529, before the arrival of Sir William Skeffington. It had been the intention of Henry VIII to marry him to Anne Boleyn, with whose family he was already connected, for a daughter of the seventh Earl had married Sir William Boleyn, and thus their son Thomas became grandfather to Queen Elizabeth.

The zealous Lancastrian sympathies of the Butlers dated from the days of the fifth Earl, James Butler (1420–61), who was knighted by Henry VI and created an English peer in 1449. He had commanded at the decisive battle of Wakefield in December 1460, and he it was who slew Richard, Duke of York, on that bloody field. But at the battle of Towton he was taken prisoner and beheaded, his estates being forfeited for a time; though, with the exception of the Essex properties, they were afterward restored to his brother and successor, Sir John. Thomas, the seventh Earl, was reputed to be the richest subject of the Crown; on his death he left £40,000 in money, and besides his Irish estates he possessed seventy-two manors in England. He was the only Irish peer whom Henry VII or Henry VIII had called to the House of Lords. His family had a high tradition for good looks and nobility of bearing.

Edward IV used to say of his elder brother, Sir John Butler, the sixth Earl, that “he was the goodliest knight he ever beheld and the finest gentleman in Christendom; and that if good breeding, nurture, and liberal qualities were lost to the world, they might all be found in the Earl of Ormonde.” He was a man of European culture, with a thorough understanding of many languages, and had served as ambassador at nearly every European Court. He resigned his earldom to his brother Thomas, and went on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, dying on the way in 1478.

Such was, in brief, the history of the family into which Margaret FitzGerald married. Her husband, Sir Piers, was the third son of Sir James Butler, his two elder brothers being illegitimate, and his mother was Sabh Kavanagh, of whom we have already spoken. He was a man of ungovernable temper, spending his life in suppressing Irish rebellions and warring with Desmond and Kildare in turn. The Talbots got him removed in 1524, but the King, Henry VIII, appointed him Lord Treasurer in Ireland. “No man,” it was said, “dare complain of Kildare except Ormonde.”

In 1527 he surrendered the earldom to Sir Thomas Boleyn, the grandson of the seventh Earl, and was created instead Earl of Ossory, but the older title was restored to him. With the help of his energetic wife he brought over weavers and artificers from Flanders and established industries for the production of tapestries, carpets, diapers, etc.[14] His eldest son was created Viscount Thurles in 1535 and later became ninth Earl of Ormonde. But he was the victim of unjust suspicions of hostility to the Government and was destined to fall in a mysterious way by poison at Ely House, Holborn, in 1546. His son Thomas, who succeeded to the earldom, was the famous “Black Earl,” who played a leading part in Elizabeth’s reign.

Through the whole of the later life of the eighth Earl of Kildare and the earldom of the ninth Earl the old jealousies between the great families disturbed the country, each house resenting any advance in power bestowed on the other. But during the life of the Great Earl of Kildare, all the efforts of the Ormondes did not succeed in overthrowing his authority. His readiness to confess his faults, backed by his immense influence in his own country, always extricated him from difficulties. He emerged not only unscathed, but with added marks of royal favour. He was Deputy, with breaks, under Edward IV, Richard III, Henry VII (who playfully nicknamed him his “rebel”), and Henry VIII, though the frequent changes in the succession to the English throne made the task of remaining loyal a difficult one.

Through the unceasing machinations of his old foe, the Bishop of Meath, he was captured in Dublin and committed to the Tower, where he remained two years; his wife, who was devoted to her husband, died of grief. Brought at length before the Council, at which the Bishop of Meath was his chief accuser, Kildare’s ready wit had the effect of embarrassing his enemies and amusing the King. Accused of having set fire to the cathedral of Cashel, he exclaimed, “By my troth, I would never have done it but that I thought the Bishop was in it.” He added that the Bishop, being a learned man, might easily outdo him in argument, on which the King humorously replied that Kildare was at liberty to choose a counsellor, but that “it behoved him to get counsel that was very good, for he doubted that his cause was very bad.” “I will choose the best in England,” quoth the Earl, “the King himself; and by St Bride I will choose no other.” “A wiser man might have chosen worse,” replied the King.

The Bishop, feeling that he was getting the worst of the argument, exclaimed angrily, “All Ireland cannot rule this man.” “Then shall he rule all Ireland,” replied the King. He was restored to all his estates and honours and sent back as Deputy, but his eldest son, Gerald Oge, was held in pledge for his father’s fidelity.[15]

The chief event in Kildare’s later life was the battle of Knocdoe, “the Hill of the Battle-axes” (1504), about five miles from Galway, an Anglo-Norman contest in which nevertheless “all the Irish in Ireland” are said to have been involved. It was a battle unequalled for its losses, the O’Kellys, his allies, especially suffering severely. The Irish and the Burkes were so discouraged that they surrendered Galway without resistance, and Henry bestowed the Garter on Kildare as a reward for his victory. On returning to the Pale, he distributed thirty tuns of wine among his soldiers. The old Earl died in 1513 from the effects of a shot from one of the O’Mores of Leix, and he was buried in state in the choir of Christ Church Cathedral, in a tomb which now no longer exists.

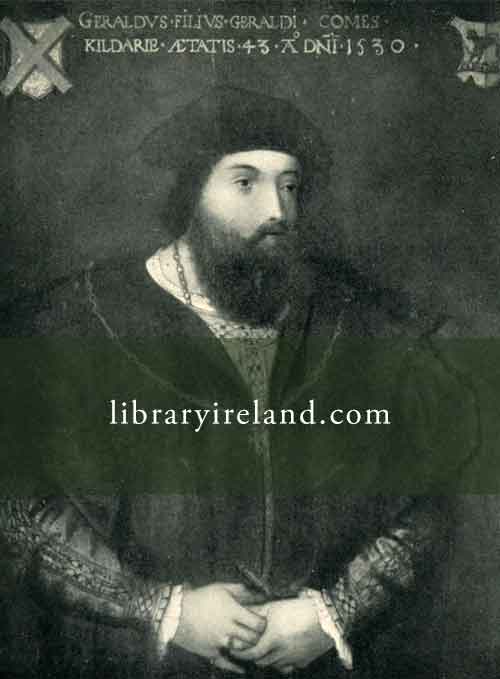

Garrett Oge (Gerald), Ninth Earl of Kildare

From a portrait at Carton, Maynooth

His son Gerald, or Garrett Oge FitzGerald, succeeded him as ninth Earl, one of the handsomest men of his day and a fighter like his father. The Annals of the Four Masters speak of him as the most illustrious of the English and Irish of Ireland in his time, his fame and exalted character being heard of in distant countries by foreign nations, as well as being spread through Ireland.

Like most of the young Anglo-Irish nobles of his period he had been educated in England, while he was detained as hostage for his father’s fidelity. He was a man of learning and interested in books, for he encouraged the writing of chronicles and kept one Philip Flattisbury for this purpose at a town near Naas. He collected a considerable library of Latin, French, English, and Irish books, of which a list still remains.[16]

A volume called The Earl of Kildare’s Rental also exists showing the methodical care with which his estates were managed. He followed his father’s example in attacking and subduing the Irish chiefs on the borders of the Pale; he relieved his own country of cess and improved his lands. He was appointed Lord Deputy on the death of his father, and in 1519 he accompanied King Henry VIII, then in the prime of his youth and splendour, to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, where Kildare was distinguished by his brilliant appearance and bearing. But his successes awakened the jealousy of his enemies, and secret reports of maladministration were sent over to London and were eagerly seized upon by Wolsey, who desired his downfall. He was summoned to England, where he married as his second wife a near kinswoman of the King, the Lady Elizabeth Grey, daughter of the Marquis of Dorset. The influence which he gained by this marriage placed him close to the Court, and in October 1520 the King wrote to the Earl of Surrey, who had replaced Kildare in Ireland, that they had “noon evident testimonies” to convict the Earl, who was accordingly acquitted and returned to Dublin in 1523.