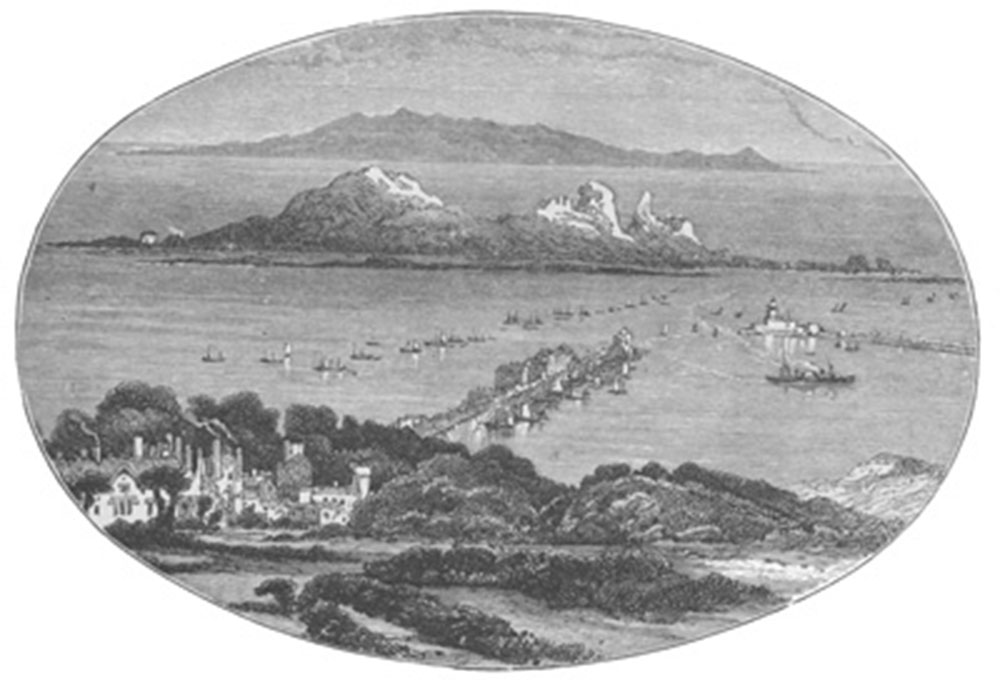

Ireland’s Eye - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter 1: Ireland’s Eye

« Previous Page | Book Contents | Next Page »

IRELAND'S EYE is the name of a rocky islet standing over against Howth Harbour, for many years the port of Dublin and the chief approach by sea to that capital. Kingstown and North Wall have superseded Howth Harbour; the rocky islet is now seen to advantage only by those who explore Howth itself; nevertheless the island's name is no bad description of Dublin. The great city is in more senses than one Ireland's Eye. Through it the Emerald Isle receives many of her impressions of the outer world, and no fairer feature in her wealth of natural beauty does she possess than the noble bay of Dublin, with the great city nestling beneath the bold headlands of Killiney and the Hill of Howth.

The first impression made upon the mind of the observer by Dublin is one of disappointment. The city hardly seems to live up to its environment. The scenery of the bay is very lovely, whether seen in the early morning or the late evening of a summer's day; the view up the Liffey as the steamer approaches the North Wall, embracing the river, the crowded masts and boats, the fine dome of the Custom House in the near foreground, and the multitudinous roofs and spires of the city in the distance, is enticing, and whets the appetite and expectations of the explorer. But here as elsewhere the close inspection does not, at any rate at first, realize the distant promise. It is not easy to define exactly the effect produced as one makes the acquaintance of the quays, Sackville Street, St. Patrick's Cathedral, Merrion Square, and College Green. There are handsome buildings, wide streets, spacious squares, many evidences of life, prosperity and abundance, and yet something seems lacking. Dublin is not like London, New York, Paris, or Amsterdam. In these great cities, differing widely as they do in manifold respects from each other, the evidences of prosperity predominate; in Dublin, although she shares many of the best qualities of her larger sisters, the stranger, although he may have a firm conviction that better times are coming, hesitates to assert that she is manifestly prospering.

While this impression is strong, the visitor can readily imagine that many take an early and sometimes incurable dislike to Dublin. The signs of apparent poverty are plentiful; the streets and buildings that really please the eye are few, the number of ragged children seems abnormal; and if the visitor to St. Patrick's or Christ Church devotes any attention to the neighbourhoods of these noted buildings, he meets many interesting but not altogether pleasing pictures of human life. Yet the writer gladly admits that Dublin's power to impress him favourably increased with each successive visit. As he came to know her better, he grew to like her more, and to appreciate more fully the beauty of her surroundings, and the special objects for which she claims recognition. And it is now time to turn to some of these.

Dublin is in the first place a considerable port. The Liffey, the quays, the docks and the canals are among the most prominent features of the metropolis. It is from the river, indeed, that she gets her name as well as a large portion of her wealth. The ancient high road from Tara to Wicklow crossed the river at this point in very early days by means of a rough wicker or hurdle bridge. Naturally a city grew up around the bridge or ford, and the name for Dublin in the Irish Annals is Ath-Cliath (pronounced Ah-clee), 'the ford of the hurdles.' Duibh-linn, 'the black pool' or 'river,' the ancient name of this part of the Liffey, gradually banished the older, and has long been the only name by which the city is known. The ancient ford is now represented by splendid bridges, the cluster of huts has expanded into square miles of brick and mortar, and the water which ages since floated the coracles of the Irish or the warships of the Northmen is now ploughed by the bulky steel ships of modern commerce. All else has changed marvellously, but in the very name of Ireland's capital there survives the sure evidence of her former humility.

Many facilities both natural and artificial exist for giving those wishful to get them good representative views of Dublin. A favourite point of view is the top of the Nelson Monument, which towers aloft in the centre of Sackville Street. Seen thence the whole city lies spread out at the observer's feet, and from that elevation, as from no other, he can also observe the beauty of the surrounding country. Some very fine distant views are obtained at different parts of the Phoenix Park. But the true citizen of Dublin maintains that the view obtained from the O'Connell Bridge is not only the best that the city can show, but is also equal to the best that any rival capital possesses. On the left bank of the Liffey, a short distance below the great bridge, stands one of the most prominent buildings in the city, viz. the Custom House.

Dublin is not only the eye but the heart of Ireland. Hence on every side are traces of the many-sided life of the nation. Her antiquity is evident in many of her names. Her former national life is recalled by the building that is now the Bank of Ireland. It was here in former days the Irish Parliament met, and here many of Curran's and Grattan's famous speeches were delivered. Her relation to England is kept prominently in view by the towers and courtyard of Dublin Castle. Her educational and literary life of the last three centuries has largely centred in Trinity College, which fronts boldly and closely upon an open space in the very heart of the city, the famous College Green. To her great religious hero is dedicated one of her two ancient cathedrals, and though the statement that St. Patrick founded it is mere fancy, it is fitting that he should for centuries have been thus associated with the metropolitan life. In the centre of College Green, and facing the fine facade of Trinity College, stands the statue of Grattan, while before the gateway of the great university, fronting the effigy of Ireland's renowned orator, are placed statues of Edmund Burke and Oliver Goldsmith. Brilliant political oratory, fervid patriotism, noble eloquence, far-seeing statesmanship, and undying literary fame are here concentred and kept continually before the eyes and the minds of the multitudes who daily throng Grafton Street and College Green.

And indeed here is the true heart of Dublin. Much of the business of the city is carried on in this district; much of her intellectual activity here finds its home and field of work; the financial heart of the country throbs here, and here blend the associations of the present and the memories of the past in stronger and more vigorous union than elsewhere.