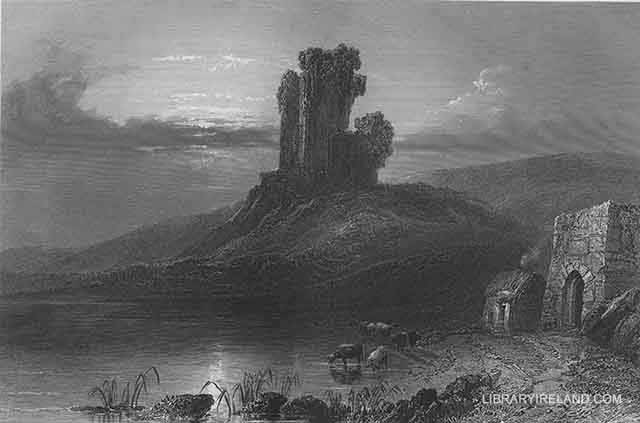

Kilcolman Castle

While I am upon the subject of places rendered famous by the residence of celebrated poets, I must not pass by unnoticed KILCOLMAN CASTLE, where Spenser, the gifted child of song, composed his inimitable Faerie Queene, and other poems of great merit. The description of a castle in the county of Cork may appear to be unaptly introduced here; but my readers will, I trust, excuse the violation of the unity of place, for the sake of bringing into proximity two poets who have celebrated in sweetly descriptive verses the rural scenery of Ireland.

I confess that I could not view the ruins of this noble castle, within whose deserted walls the proud Desmonds once held sway, and which more recently had been the dwelling-place of one of England's most accomplished poets, without a feeling of deep sadness. The desolate pile, resting in lonely grandeur on the banks of the "Mulla fair and bright," seemed brooding over its vanished greatness; while the poet's favourite stream murmured sadly as it rolled along. It will be recollected by those who have read Spenser's biography, that he was one of those English settlers to whom Elizabeth granted the forfeited estates of Munster, on condition that no Irish should be permitted to live upon them. The result of this impolitic and impracticable design, as might be foreseen, was to increase the hatred with which the Irish naturally regarded these intruders, and to expose the latter more effectually to the vengeance of their enemies. Spenser had obtained, in 1586, a grant of three thousand acres of land, part of the forfeited estates of the Earl of Desmond:—the following year he took up his residence in his Castle of Kilcolman, and in the favourable retirement of its ancient walls, or wandering along the banks of his beloved Mulla, he composed his beautiful poem of The Faerie Queene, a work which, for brilliancy of fancy and richness of thought, is unequalled by anything of a similar nature in the English language. Throughout his poems we find numerous allusions to the scenery in the neighbourhood of Kilcolman and of Castletown Roche, where he possessed another small estate.

Spenser, it should be observed, especially describes Ireland as a country formerly of such "wealth and goodness," that the gods used to resort thereto for "pleasure and for rest;" his muse expatiates upon the beauty of her rivers and mountains, and of the delicious verdure of the

——"Woods and forests which therein abound,"

but with all his poetical admiration of the scenery of the country, he displays, in his View of the State of Ireland, a decided dislike and prejudice against the people, and there can be no doubt that the antipathy was mutual. When the rebellion of Tyrone broke out in 1598, Spenser was compelled to fly to England to escape the fearful retaliations which were everywhere being directed against the English settlers. He saved his life; but his castle was burned, and all his property plundered by the rebels. It is not therefore surprising that he should have written with acrimony against the Irish, whom he regarded as natural and implacable enemies—overlooking the fact that he had himself been in the first instance a party to the indefensible policy of England, in her barbarous design of crushing and exterminating the people of a whole province.

Mr. Trotter, an eccentric but benevolent man, who made a pedestrian tour of Ireland in the year 1814, remarks, that amongst the peasantry of this neighbourhood "the name and condition of Spenser is handed down traditionally, but they seem to entertain no sentiment of respect or affection for his memory;" and, again, in speaking of some engaging traits in the character of the Irish, he says, "It is somewhat surprising that Spenser appears not to have appreciated their good qualities as they merited; but he spoke not their language, and came to their country full of prejudice against them."

The situation of the castle is bleak and cheerless, the surrounding mountains being completely destitute of timber—although a tradition exists that the woods of Kilcolman extended to Buttevant, three miles distance. The estates have long since passed away from the poet's family, who are now supposed to be extinct. The chief portion of the property was forfeited by a grandson of Spenser's, through his attachment to the cause of the unfortunate James II.

This digression done, we return to Lissoy, and, with a parting glance at its peaceful bowers, resume our route towards Dublin.