Ancient Irish Houses

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVI....continued

There were windows in the fraig or wall, and often a skylight in the roof. Glass was known among various ancient nations from the most remote period: the Celts of Britain were well acquainted with it: and from constant references to it in our oldest writings, it is obvious that it was well known to the ancient Irish.

FIGS. 76, 77, 78. Glass and porcelain ornaments, full size, now in the National Museum. In figs. 76 and 77 the coloured ornaments form part of the substance, and were worked into shape, with great skill, while the whole mass was softened by heat. Fig. 76 of clear glass, with yellow spiral ornament. Fig. 77, pin-head of fine light red porcelain decorated with wavy stripes, some white, some yellow: found with part of bronze pin attached as shown in figure. There are in the Museum many ornaments of coloured glass with variously coloured patterns of enamel on the surface of which the most beautiful is shown, full size, in fig. 78. It is a flat circular disk, half inch thick the body of dark blue glass, with a wavy pattern of white enamel, like an open flower, on the surface (All from Wilde's Catalogue).

Beads and other small ornamental objects of glass, variously coloured, are constantly found in Irish pre-Christian graves and crannoges. All the objects of this kind wherever found in Ireland were formed while the material was heated to softness.

Moreover, the manufacture of these little articles was an art requiring long training and much delicate manipulative skill, for most of them are made of different-coloured glass or porcelain—blue, white, yellow, pale red, &c.—blended and moulded and beautifully striated in the manner shown imperfectly in the black-and-white figures on the opposite page. They were used for ornamentation, very often forming the heads of pins, but sometimes made into rings, or strung together for beads.

Glass drinking-vessels were known to the Irish at least as early as the sixth century; and they are frequently mentioned in the most ancient of the tales. Add to all this that the remains of a regular glass factory have been found in the county Wicklow, where great quantities of lumps of glass, chiefly of the three colours, blue, green, and white, have been—and can still be—dug up.

Glass was used in England for church windows in the seventh century; and it had been long previously in use for this purpose on the Continent: so we may conclude that the knowledge of the use of glass for windows found its way into Ireland from Gaul, Italy, and England, through missionaries and merchants. At all events glass windows are mentioned in many of the ancient Irish tales, which shows that this use of glass was familiarly known to the original writers.

There was one large door leading to the principal apartment of the dwelling-house, with smaller doors, opening externally, for the other rooms. Generally the several rooms did not communicate with each other internally, In the outer lis or rampart surrounding the homestead (for which see farther on), there was a single large door. The common Irish word for door was, and is, dorus a single leaf of a door was comla. The knocker was a small log of wood called bas-chrann, i e. 'hand wood,' which lay in a niche by the door. It is everywhere mentioned in the old tales that visitors knocked with the bas-chrann.

FIG. 79. Carrickfergus Castle: one of the Anglo-Norman strongholds referred to in this chapter. (From the Dub. Pen. Journ., I. 113.).

In rich people's houses there was a special doorkeeper to answer knocks and admit visitors. At the bottom of the door was a tairsech or threshold. The jamb was called ursa: the lintel was for-dorus (i e. 'on the door'). On the outside of the large door of the lis was a porch called aurduine (lit. 'front part of the dún'). Cormac's Glossary explains aurduine as a structure "at the doors of the dúns, which is made by the artisans"—implying ornamentation. The lis door was always closed at night.

The door was secured on the inside either by a bolt or by a lock. We have the best evidence to show that locks were used in Ireland in very early times. Mention is made of the aradh [ara] or ladder, which must have been in constant use

FIG. 80. King John's Castle in Limerick. Erected in the beginning of 13th century by one of the Anglo-Norman chiefs. Some authorities state that it was built by the order of King John. One of the Anglo-Norman castles referred to farther on. (From Mrs. Hall's Ireland).

The houses were generally small, according to our idea of size. But then we must remember that, like the people of other ancient nations, the Irish had very little furniture, In the main room there was probably nothing—besides the couches—but a sufficient number of small movable seats and a large table of some sort, or perhaps a number of small tables. Moreover the standard of living was in all countries low and rude compared with what we are now accustomed to—a fact that ought to be borne in mind by the reader of the account given here of the domestic arrangements in ancient Irish houses. In England, even so late as the time of Holinshed—sixteenth century—hardly any houses had chimneys. A big fire of logs was kindled against the wall of the principal room, the smoke from which escaped through an orifice in the roof right overhead. Here the meat was cooked, and here the family dined. In very few houses were there beds or bedrooms; and the general way of sleeping was on a pallet of straw covered with a sheet, under coverlets of various coarse materials, with a log of wood for a pillow: while the manner of eating, which is noticed farther on, was correspondingly rude. All this is described for England by a trustworthy English writer named Roberts.

We know that many of the great houses were very large. The present remains of the Banqueting-Hall of Tara measure 759 feet long and 46 feet wide: and Petrie states that it must have been originally much wider. We are told that the measurement of the hall of Emain was "fifteen feet and nine score" (195 feet): which refers to a square shape.

We may form some idea of the better class of dwellings from an enumeration, in one of the law books, of the various buildings in the homestead of a well-to-do farmer of the class bo-aire, who rented land from a chief, and whose property was chiefly in cattle.

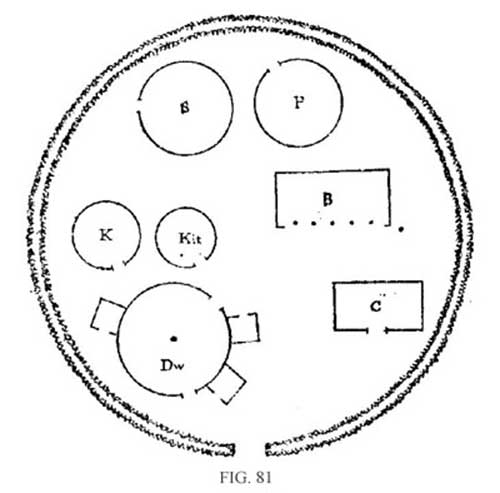

FIG. 81. Conjectural plan of homestead of a well to do farmer of the bo-aire class, constructed from descriptions given in Brehon Laws. "Dw," family dwelling house of wickerwork, 27 feet in diameter (at least), with three outside sleeping rooms (which might be either round or rectangular): "Kit," kitchen "K," kiln (chiefly for corn drying): "B," barn: "C," calf house: " P," pig-house: "S," sheep house. Whole group surrounded by a circular rath, with one entrance. The cows and horses were kept outside this enclosure.

His dwelling consisted of (at least) seven different houses, each, as already observed, with a separate wall, door, and roof:—1. Dwelling-house, at least 27 feet in diameter: 2. Kitchen or cooking-house, at the back of the dwelling-house: 8. A kiln for drying corn: 4. A barn in which corn was stored: 5. A sheep-house: 6. A calf-house: 7. A pig-sty, These were all in one group close together; and each generally, though not always, consisted of the usual round-shaped wicker-house with conical roof: the whole group being surrounded by the lis or rath, described farther on. In all houses of the more comfortable class, the kitchen was separate from the dwelling-house and placed at the back: and there was a separate pantry for provisions. The barn was oblong and had one side quite open, with the roof supported at that side on posts.

The women had a separate apartment or a separate house in the sunniest and pleasantest part of the homestead. This was called a grianan [greenan], which signifies a summer-house: a diminutive derivative from grian, 'the sun.' The women's greenan is constantly mentioned in Irish writings. In Croghan the greenan was placed over the for dorus or lintel, as much as to say it was placed in front over the common sitting-room: and probably it occupied some such position in most houses. In great houses there was one apartment called "the House of conversation," answering to the modern "drawing-room," where the family often sat, especially to receive visitors.