The Field of Boliauns - Fairy Legends of Ireland

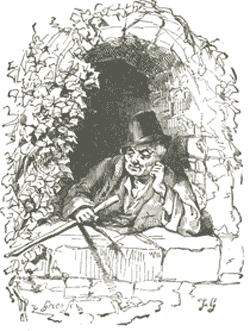

OM FITZPATRICK was the eldest son of a comfortable farmer who lived at Ballincollig. Tom was just turned of nine-and-twenty when he met the following adventure, and was as clever, clean, tight, good-looking a boy as any in the whole county Cork. One fine day in Harvest—it was indeed Lady-day in harvest, that everybody knows to be one of the greatest holidays in the year — Tom was taking a ramble through the ground, and went sauntering along the sunny side of a hedge, thinking in himself, where would be the great harm if people, instead of idling and going about doing nothing at all, were to shake out the hay, and bind and stook the oats that were lying on the ledge, especially as the weather had been rather broken of late, when all of a sudden he heard a clacking sort of noise a little before him, in the hedge. "Dear me," said Tom, "but isn't it now really surprising to hear the stonechatters singing so late in the season?" So Tom stole on, going on the tops of his toes to try if he could get a sight of what was making the noise, to see if he was right in his guess. The noise stopped; but as Tom looked sharply through the bushes what should he see in a nook of the hedge but a brown pitcher, that might hold about a gallon and a half of liquor; and by-and-by a little wee diny dony bit of an old man, with a little motty of a cocked hat stuck upon the top of his head, a deeshy daushy leather apron hanging before him, pulled out a little wooden stool, and stood up upon it, and dipped a little piggin into the pitcher, and took out the full of it, and put it beside the stool, and then sat down under the pitcher, and began to work at putting a heel-piece on a bit of a brogue just fitting for himself. "Well, by the powers," said Tom to himself, "I often heard tell of the Cluricaune; and, to tell God's truth, I never rightly believed in them—but here's one of them in real earnest. If I go knowingly to work, I'm a made man. They say a body must never take their eyes off them, or they'll escape."

Tom now stole on a little further, with his eye fixed on the little man just as a cat does with a mouse, or, as we read in books, the rattlesnake does with the birds he wants to enchant. So when he got up quite close to him, "God bless your work, neighbour," said Tom.

The little man raised up his head, and "Thank you kindly," said he.

"I wonder you'd be working on the holiday?" said Tom.

"That's my own business, not yours," was the reply.

"Well, may be you'd be civil enough to tell us what you've got in the pitcher there?" said Tom.

"That I will, with pleasure," said he; "it's good beer."

"Beer!" said Tom; "Thunder and fire! where did you get it?"

"Where did I get it, is it? Why, I made it. And what do you think I made it of?"

"Devil a one of me knows," said Tom, "but of malt, I suppose; what else?"

"'Tis there you're out. I made it of heath."

"Of heath!" said Tom, bursting out laughing; "sure you don't think me to be such a fool as to believe that?"

"Do as you please," said he, "but what I tell you is the truth. Did you ever hear tell of the Danes?"

"And that I did," said Tom; "weren't them the fellows we gave such a licking when they thought to take Limerick from us?"

"Hem!" said the little man, drily, "is that all you know about the matter?"

"Well, but about them Danes?" said Tom.

"Why all the about them there is, is that when they were here they taught us to make beer out of the heath, and the secret's in my family ever since."

"Will you give a body a taste of your beer?" said Tom.

"I'll tell you what it is, young man, it would be fitter for you to be looking after your father's property than to be bothering decent, quiet people with your foolish questions. There now, while you're idling away your time here, there's the cows have broke into the oats, and are knocking the corn all about."

Tom was taken so by surprise with this that he was just on the very point of turning round when he recollected himself; so, afraid that the like might happen again, he made a grab at the Cluricaune, and caught him up in his hand; but in his hurry he overset the pitcher, and spilt all the beer, so that he could not get a taste of it to tell what sort it was. He then swore what he would not do to him if he did not show him where his money was. Tom looked so wicked and so bloody-minded that the little man was quite frightened; so, says he, "Come along with me a couple of fields off, and I'll show you a crock of gold."

So they went, and Tom held the Cluricaune fast in his hand, and never took his eyes from off him, though they had to cross hedges, and ditches, and a crooked bit of bog (for the Cluricaune seemed, out of pure mischief, to pick out the hardest and most contrary way), till at last they came to a great field all full of boliaun buies (rag-weed), and the Cluricaune pointed to a big boliaun, and says he, "Dig under that boliaun, and you'll get the great crock all full of guineas."

Tom in his hurry had never minded the bringing a spade with him, so he thought to run home and fetch one; and that he might know the place again he took off one of his red garters, and tied it round the boliaun.

"I suppose," said the Cluricaune very civilly, "you have no further occasion for me?"

"No," says Tom; "you may go away now, if you please, and God speed you, and may good luck attend you wherever you go."

"Well, good-bye to you, Tom Fitzpatrick," said the Cluricaune, "and much good may it do you, with what you'll get."

So Tom ran, for the dear life, till he came home and got a spade, and then away with him, as hard as he could go, back to the field of boliauns; but when he got there, lo, and behold! not a boliaun in the field but had a red garter, the very identical model of his own, tied about it; and as to digging up the whole field, that was all nonsense, for there was more than forty good Irish acres in it. So Tom came home again with his spade on his shoulder, a little cooler than he went; and many's the hearty curse he gave the Cluricaune every time he thought of the neat turn he had served him.