The Munster Planters (2)

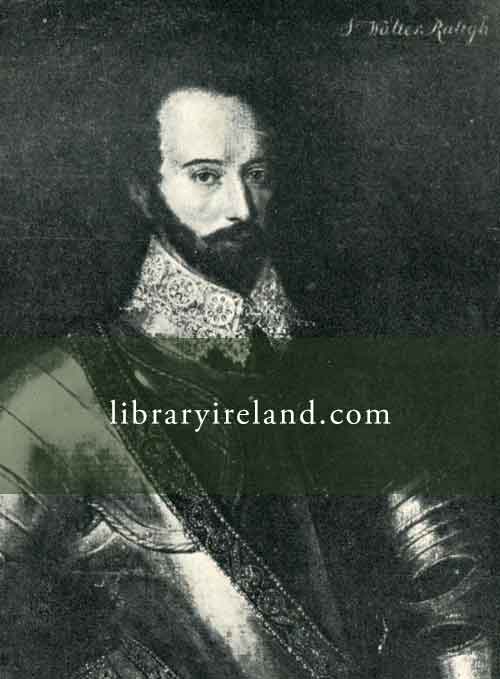

Sir Walter Raleigh

From a portrait at Wimpole

Besides his immense grants of lands Raleigh received the patronage of the Wardenship of the College of Our Lady at Youghal, with the exclusive rights to the valuable salmon fishery in the tidal waters of the Blackwater.

The rich soil that stretched along both banks of the river was waste and neglected, and Raleigh was not the man to improve it. His restless nature and vain disposition looked for more rapid means of raising his fortunes than the laborious cultivation of the lands that had fallen, by Court favour, into his hands.

Brilliant, stirring, and extravagant, even judged by the standards of Elizabeth’s day, the man who sunned himself in Court smiles, and clad himself in cloaks and shoes heavy with pearls or diamonds, must have found the quiet of the beautiful little town of Youghal, with its memories of collegiate and monastic retirement, irksome to his nature.

Raleigh’s residence at Youghal was not his first visit to Ireland. He had come over in his youth as a needy Munster captain in that small band of horse which was commanded by his half-brother and fellow-adventurer Sir Humphrey Gilbert. That band, fresh from the ruthless wars of Languedoc, where Raleigh had seen the unfortunate peasants smoked out of the caverns in the mountains where they had taken refuge, only to fall upon the swords of the soldiery, brought to Ireland the same brutal instincts of warfare. Let loose upon Munster these young Captains did mischief altogether out of proportion to their numbers.

Raleigh’s first act had been in connexion with the execution at Cork in August 1580 of James FitzGerald, younger brother to the Earl of Desmond, and his next was the slaughter of the Spaniards and Irish at Smerwick, when he and Mackworth were sent in “to do execution” on the inmates.

Raleigh held firmly the common belief of the day that all means were justifiable in dealing with rebels and that pity to the Spaniards who aided them was treachery to the State. But his harsh methods often defeated their ends; his capture of Barry’s Court turned the wavering Lord Barry into an open enemy, and even for that age Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s methods “had a little too much warmth and presumption,” so that he had been replaced in the Presidency of Munster by Sir John Perrot.

Their company was paid off and disbanded in December 1581, and Raleigh returned home. When he went back again in 1590–91 he was no longer captain of a troop of horse, but a Court favourite with large English properties, estates forfeited after the Babington conspiracies. He was Lord Warden of the Stannaries, and Captain of the Queen’s Band; to these emoluments he added his great acquisitions in Cork. It was now that he found his friend Edmund Spenser at Kilcolman Castle, “under the foote of Mole, that mountaine hore,” sitting, “alwaies idle,” beside the restless waters of his loved Mulla stream, looking out on the distant Cork and Kerry ranges, and writing his immortal poem, while events like the Armada passed him by unheeded.

Spenser came over to Ireland in 1580 as private secretary to Lord Grey de Wilton, and from that time forward most of his life was passed in that country. He held several appointments, being in 1581 made Clerk of Degrees and Recognizances in the Irish Court of Chancery, and, seven years later, Clerk to the Council of Munster. He had a great admiration for Lord Grey, whom all, he says, knew to be “most gentle, affable, loving and temperate, but that the necessity of that present state of things enforced him to violence, and almost changed his natural disposition,” and he warmly resented the charge that Grey broke his word at Smerwick. But he fully approved of Grey’s short and sharp methods of conquest and resettlement, and blamed the changes of policy and the weakness and corruption of governors “who thought more of their own ease and advancement than of the good of the State and country.”[5] In the fifth book of The Faerie Queene Lord Grey de Wilton appears as Artegall, “the Champion of true Justice,” whose “wreakfull hand” none could abide. He is attended by Talus,

made of yron mould,

Immovable, resistlesse, without end;

Who in his hand an yron flail did hould,

With which he thresht out falshood, and did truth unfould.

The Faerie Queene was written at Kilcolman, a castle belonging to the Desmond family, which seems to have passed into his hands, with a grant of 3028 acres in Co. Cork, sometime after 1586. Kilcolman, now a ruin, was placed in a plain which commanded a wide view, shut in by the Ballyhowra Mountains to the north and by the Kerry Hills to the west. Here,

Under the foote of Mole, that mountaine hore,

Keeping my sheepe amongst the cooly shade

Of the greene alders by the Mullaes shore,[6]

he wandered and sang in a solitude which at times was cheered by the visits of the “Shepherd of the Ocean,” Sir Walter Raleigh.

To an Irish reader Spenser’s poems take a largely added interest from the fact that the incidents and the scenes he depicts reflect the conditions and scenery of Munster at a critical moment of its history. The startling pictures of wild life encountered by his knights are probably not greatly exaggerated reflections of actual stories brought to his ears. They approached all too nearly to the facts of life around him. On the outbreak of the second Desmond rebellion in the autumn of 1598 the insurgents wreaked their vengeance on him for his occupation of Kilcolman Castle by plundering and burning it to the ground. It is said by Ben Jonson that one of his babes perished in the flames. In poverty and deep distress Spenser returned to London, where he died shortly afterward.[7]

A figure very familiar in the neighbourhood of Youghal in the time of Spenser and Raleigh was that of the aged Dowager Countess of Desmond, about whom strange traditions floated. Widow of a man who, in 1529, had become Earl of Desmond at the age of seventy-five, and having survived him for seventy years, it is not strange that the ‘Old Countess’ became one of the wonders of her age.

The Old Countess of Desmond

From a portrait at Knole

Rumour said that she was born in 1464, that she had been maid of honour at the Court of Edward IV (d. 1483), and that she had danced with Richard III when Duke of Gloucester, of whom she retained memories much more favourable than those which have come down to us. Her husband, Sir Thomas the Bald of Desmond, must have been sixty years of age when she married him. He was the third son of the eighth Earl, beheaded at Drogheda in 1468, and in spite of the efforts at reparation made by Edward IV, he and his brothers were in a constant state of suppressed rebellion; “with banners displayed they sought revenge.”

The Earl, who seems to have been an eccentric, had divorced his first wife, Sheela MacCarthy of Muskerry, to marry Katherine, who was eldest daughter of Sir John FitzGerald, Lord of Decies, and his cousin; he had on his hands the blood both of his late father-in-law and his first wife’s brother. The castle of Inchiquin, where he and Katherine lived, must have seen wild deeds. He was so distrustful of strangers that, instead of bed and board, he provided a halter for them outside his walls “as though all visitors were spies and wizards.” He took full advantage of the system of coign and livery instituted by his ancestor, the first Earl of Desmond, for he lived half the year upon his tenants; and he refused to pay one groat of yearly revenue to the Crown, in spite of his immense possessions in Waterford, Limerick, Cork, and Kerry, or to obey any of the King’s laws.

Henry VIII ordered the Earl of Ossory in 1534 to curb this fierce and grasping man, but he died in the same year at the age of eighty, leaving a grandson by the son of his first wife, who was brought up at the English Court and educated in the royal household. Disloyal Geraldines dubbed him “the Court Page” Earl, and he was subsequently murdered by Sir Maurice Dubh, or Duff, “the Black Geraldine,” “a man without faith or truth, cruel, severe, merciless,” whose murder of the “Court Page” Earl was the first step “to the overthrow of this honourable house of Desmond, God in revenge thereof not leaving one of the race of Sir John or Sir Maurice alive upon the face of the earth.” Sir Maurice’s son was the James FitzMaurice who aided Earl Garrett’s rising.

After the death of her turbulent spouse the Countess lived on at Inchiquin Castle near Youghal, which had long been looked upon as a dower house for widows of the Earls of Desmond. She made over the property to Garrett, Earl of Desmond, then out in rebellion, but after his attainder it was granted to Raleigh, who recognized her prior claim in two leases drawn up by him. He knew personally the aged lady, who lived not many miles from his house at Youghal.

When Boyle obtained Raleigh’s lands the old Countess of Desmond, whose jointure came to an end at the age of the ‘trust term’ of ninety-nine years, leaving her reduced to penury, was obliged to revisit the Court to lay her case before Queen Elizabeth and prove her identity. She was accompanied by her daughter. Landing at Bristol, tradition says that the old lady “came on foot to London, as she was wont to walk weekly at home to Youghal on market-days. But her daughter being decrepit, was brought in a little cart, their poverty not allowing better means.”

Her appearance at Court created a sensation, and is mentioned in many of the memoirs of the day. Bacon says that tradition gave her sevenscore years, and Raleigh in his History of the World says, that she was alive in 1589 and “many years afterwards, as all the noblemen and gentlemen in Munster can testify.”[8]

She lived on till 1604, thus outliving at least three—tradition would make it six—of the Queen’s ancestors and Elizabeth herself. She witnessed the great power and the downfall of the house of Desmond, caused partly through the misdoings of Englishmen, but largely also by the disregard of all laws, human and divine, by her husband and his kindred. She is said to have died from a fall while picking cherries from a tree in Raleigh’s garden.

Raleigh himself, in later life, after making experiments in plantations in other lands than Ireland, was condemned to spend twelve mournful years in the Tower of London, during some part of which another apartment in the same gloomy pile was occupied by the last of the Desmonds, the spoiler and spoiled being thus brought to one fate together.

Like Florence MacCarthy, Raleigh endeavoured to while away the tedium of imprisonment by planning a history, and he carried out the compilation of his History of the World. Florence’s tract is a mere fragment, addressed to the Earl of Thomond, and mainly intended to prove that the Irish came from Greece.[9]

At Youghal Raleigh made attempts to grow the potato and tobacco. His long imprisonment ended in his death on the scaffold—a fate that seemed to fall, like the judgment of God, on all those who held in their hands the weal and woe of Ireland, and who betrayed their trust.

Among the ‘adventurers’ who built up the largest fortunes out of the escheated lands were Sir Valentine Brown, who bought up large slices of the MacCarthy estates from the spendthrift Earl of Clancar, and Sir Richard Boyle, first Earl of Cork, a man who arrived in Dublin in 1588 with £27 in his pocket, and who died leaving his family possessed of immense wealth, his daughters intermarried with the highest nobility, and three of his sons ennobled.

The rapid acquisition of wealth by the clever and unscrupulous Boyle was so surprising that the Queen believed that he was in receipt of foreign supplies; but the easier method of ‘finding lands by concealments’ provided all the means that Boyle required. He was imprisoned in 1594, and in the Munster rebellion he lost all his possessions, but such was his plausibility that he won over the Queen and was sent back as Clerk of the Council of Munster under Sir George Carew, and from this time his talents and energy ensured his rapid rise. To him it fell to convey to London the news of the victory of Kinsale, and it is characteristic of his enterprise that, leaving Shannon Castle about two o’clock on Monday morning, he delivered his packet to Sir Robert Cecil at supper on the following day, and before seven the next morning was explaining the details of the siege to the Queen in her bedchamber. His marriage with Sir Geoffrey Fenton’s daughter was another step in his advance, and on the same day he was knighted by the then Deputy. Cecil writes to Carew:[10]

“Boyle is accused by Crosby for I know not what; of cosining and concealing; one barrell little better hearing than th’ other. Let me know therefore, whether you would have him favoured or no; truly the fellow seems witty.”

And Ormonde in December 1601 complains to Cecil:

“One Crosby and Boyle have been the only means of overthrowing many of her Majesty’s good subjects by finding false titles to their lands, and turning them out. … By that means they got much lands for themselves, which manner of dealing brought much discontentment and sedition amongst the subjects.”[11]

From a material point of view, Boyle, soon to be created Earl of Cork, set about the improvement of his estates with vigour and success, building castles, bridges, schools, almshouses, and towns, and making such great improvements that Cromwell, when he visited the South, wished there had been an Earl of Cork in every province. He had, in fact, transformed great portions of the South from a desert into flourishing modern cities.